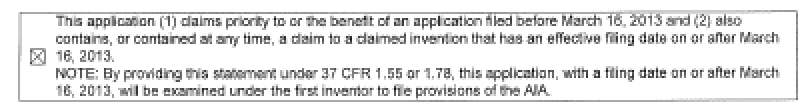

We are familiar with the “check-the-box” problem. The AIA provides that for a “transition” application, the law to be applied to determine what is patentable and what is not patentable is based on whether the application contains, or ever contained, at least one claim the effective filing date of which is on or after March 16, 2013. (A “transition” application is an application filed on or after March 16, 2013 that claims domestic benefit or foreign priority from an application filed prior to March 16, 2013.) The AIA did not say who exactly is supposed to figure out whether such a claim exists or existed. Unfortunately for applicants, in the February 14, 2013 Final Rules the USPTO successfully shifted this claim analysis burden to the applicant (more accurately, to the patent practitioner).  It falls to the practitioner to work out whether or not this box should be checked. And years later in litigation of such a transition application, it will often happen that an accused infringer will devote enormous amounts of time and energy exploring whether a case can be made the the practitioner made a check-the-box mistake — checking the box when it should not have been checked, or failing to check the box when it should have been checked.

It falls to the practitioner to work out whether or not this box should be checked. And years later in litigation of such a transition application, it will often happen that an accused infringer will devote enormous amounts of time and energy exploring whether a case can be made the the practitioner made a check-the-box mistake — checking the box when it should not have been checked, or failing to check the box when it should have been checked.

Which gets us to the topic of this blog posting. What if, during the pendency of a transition application, the practitioner discovers to his or her horror that a check-the-box mistake was made? Can the mistake be corrected? If so, how?

As best I can discern, the answer to this question seems to be very different depending on whether the mistake was checking a box that should not have been checked, or failing to check a box that should have been checked.

Which makes no sense, of course. The consequences for the Examiner of a box-checking mistake are the same regardless of whether the mistake was checking a box that should not have been checked, or failing to check a box that should have been checked. Either way, if the Examiner has already mailed at least one Office Action, any mistake about box-checking would lead to the Examiner having to go back and review the work that the Examiner had already done, in case things were to change about what is patentable and what is not.

The way it should be is that if a box-checking mistake were to be corrected at any time prior to the first office action, there should be no penalty. If, on the other hand, a box-checking mistake did not get corrected until after the first office action, there ought to be some mechanism for correcting things, perhaps accompanied with payment of a fee.

But the way it really is, is very different from the way it should be.

The February 14, 2013 Final Rules make clear that it is an extremely serious matter if the practitioner fails to check the box when it should have been checked. 37 CFR § 1.55 and 37 CFR § 1.78 provide that the checking of the box absolutely must be accomplished by the “4 and 16” date, that is, within four months of filing the application, or within sixteen months of the priority date or domestic benefit date, whichever is later. The rules allow no extension of time for this task.

The other direction, checking the box when it should not have been checked, can apparently be remedied at any time. See USPTO’s own slides on this subject, particularly slide 38 which says:

Applicant may also rescind an erroneous 1.55/1.78 statement in a separate document.

In the EFS-Web system there is a document description “Make/rescind AIA (First Inventor To File) 1.55/1.78 Stmnt” specifically for this purpose.

So the practitioner that rescinds the checking of a box may apparently do so at any time without any penalty. As far as I can see, the rescission of the checking of the box could be done up until the day before the patent issues.

In contrast, if the “4 and 16” date has come and gone, it is simply too late to check a box that had not previously been checked but should have been checked. This is so even if there has not been any office action yet.

Suppose you are one day past the “4 and 16” date, and you discover that the box should have been checked but did not get checked. What can you do?

Clearly one path would be to file a continuation application, and to make very sure to check the box within four months. This is an expensive path, and seems wholly unnecessary if no office action had been mailed yet.

Another conceivable approach would be to file a Rule 182 Petition, asking that Rule 55 or Rule 78 (as the case may be) be suspended so as to permit a correction of the failure to check the box despite the fact of the 4-and-16 date having passed.

It seems clear the USPTO did not think through how it should handle a box-checking mistake. There is no good reason why the situation should be so very assymmetrical. As things now stand a practitioner that rescinds the checking of the box may do so at any time, while the practitioner that desires to check a box that had mistakenly gone unchecked is incapable of doing so if the 4-and-16 date has passed. This despite the fact that the actual burden upon the Examiner is the same regardless of the direction of the mistake.

Part of the flaw in USPTO’s rulemaking is that the rules, if intelligently drafted, would have called for the applicant in a transition case to affirmatively indicate whether the “old law” or “new law” should be applied. The rules should have called for the applicant to check an “old law” box or a “new law” box.

Instead, the flawed rules fail to draw any distinction between (a) the applicant that studied the claims and worked out that the “old law” should be applied, and (b) the applicant that failed to give any consideration at all to whether the “old law” or “new law” should be applied. Saying this differently, the flawed rules treat silence as if it counts as an affirmative statement that it is the “old law” that should be applied.

And the flawed rules fail to recognize that it does not make any extra work for the examiner if the applicant corrects a box-checking mistake at any time prior to the first office action.

I welcome comments on all of this.

Thank you for drawing attention to this serious problem and how to approach it. I agree that it is a trap for the unwary.

Carl, I didn’t comment at the time because I was in complete agreement with you. But I would like to now add that reviewing these check boxes during intake of a portfolio is a nightmare. As you stated, there is no way to know whether the prior practitioner carefully decided not to check the box or whether they did not even realize that such a consideration existed.

I thought I’d learn how to correct a check-the-box mistake but I see that you are not quite sure how to fix it either. Filing a CON is one way of handling. And a suggestion is made to file a Rule 182 petition. A phone call to the USPTO legal department helped somewhat.

For the “we should have checked the box” they say:

No ADS needed.

Separate request making the transition statement needed.

File RCE.

Also, though some others have suggested filing the new ADS, the legal department asked us not to, saying that it’s incredibly difficult to mark-up a copy of a check box. For what it’s worth!