It took a year and a half of various efforts and dead ends, but by now I have actually figured out a way to force the fireplace in the photograph to make nice with a home automation ecosystem. It is a built-in gas-fired fireplace. This article describes the dead ands and the eventual success.

Fireplaces like this usually have crushed glass or pumice gravel across the bottom, and usually have halogen lights underneath to light up the glass bed. They usually have a forced-air blower to draw room air into a plenum so that it can be heated and returned to the room. They usually have a gas controller that uses a stepper motor or multistage valve system to permit a user to select any of various flame heights. The fireplace costs between $2500 and $5200 and of course there is an installation labor cost as well.

And nothing about the fireplace design makes nice with any ordinary home automation ecosystem. Everything is tied to a nasty proprietary remote control which you can see here:

It turns out that no matter what brand of high-end built-in gas-fired fireplace you might choose (and there are a dozen brands of such fireplaces, all costing many thousands of dollars), every fireplace maker uses a gas controller and remote control solution from a company in Italy called SIT S.p.A. This is one of those niche-market areas, I guess, where there is no profit potential for any second or third company to engineer a competing controller and remote control solution. So there is exactly one company that you are forced to go to if you want to manufacture built-in fireplaces like this. And that one company is SIT. Twenty or thirty years ago they designed this gas controller and remote control solution, and they did the approvals to get it CSA-approved (the gas safety trade association) and to work out that it can comply with every building code in the world. Having accomplished all this, SIT leaned back and decided never to spend another penny on improvements or enhancements. And they realized they could charge almost whatever they like because no other company is ever going to decide to try to enter this niche market. The replacement parts are very expensive.

Let’s start with why I hate the remote control. This is the kind of remote control where the designer of the remote control uses icons or hieroglyphs that the designer thinks are clear and easy to understand but no ordinary user could ever guess the meaning of. And the designer desperately tries to keep cost down by minimizing the actual button count, since buttons cost money and contribute to form factor. So each button is made to have at least two or three meanings. We have often seen consumer electronic device user interfaces where any particular button has at least two meanings depending on whether it receives a brief tap or a long push, or has a third meaning if you tap it twice in quick succession rather than just once. These are the sorts of things you could never guess to do, and could only learn by reading and re-reading a user manual.

This remote control is even more evil than that. This remote control has situations where any particular button has different meanings based on whether you have or have not pressed certain other buttons recently, and how many times you pressed those other buttons.

So for example look at the bottom button with the circle in it. What is your guess about the meaning of that button? Could it be the “off” button, with the circle meaning the numerical digit zero? Good guess, but no! It turns out that circle button is the one that affects the meaning of “up and down” depending on how many times you recently pressed the circle button. Depending on your recent button-pressing activity with the circle button, the up and down buttons might mean “make the halogen lights brighter or dimmer”, or the up and down buttons might mean “make the air circulation blower go faster or slower”, or the up and down buttons might mean “make the flame to be more or less flame”. Or, this remote control can be wall mounted with the goal that it will be sort of a thermostat for controlling the temperature of the room, in which case there is a button pressing history state where the up and down buttons mean “set the desired room temperature to be warmer or cooler”.

Never mind that this “thermostat” requires batteries and the batteries run out eventually. Not like your ordinary house thermostat that gets powered by wires.

Oh and never mind that inside the fireplace, the radio receiver that receives the commands from this remote control is a thing that itself runs only on batteries (four AA batteries). And they are in a place that is very hard to get at. Most homeowners would be unable to figure out how to get in there to replace those batteries when they run out. You can’t make this stuff up.

So let’s suppose you want Alexa to be able to turn the fireplace on and off. Or let’s suppose you want to let your home automation system turn the fireplace on and off. How might you tackle this?

You would, of course, start by studying the technical documentation from the fireplace manufacturer, to see whether there is some interface for home automation. Nope. Forget about it. For these fireplace manufacturers, their idea of technical documentation is a poorly worded thing that mostly tells you the shape and size of the unit and how much free space you must leave around it to comply with building codes, and what you can and cannot do in the way of a flue for the exhaust gases. But not a word about how you might somehow connect the fireplace to any external system.

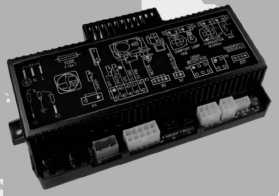

After a lot of study and poking round, you eventually work out that the fireplace manufacturer outsourced the gas controller and remote control function to this company in Italy called SIT. So the natural next step is to look at the technical documentation from SIT about its gas controller and its remote control solution. Nope. Forget about it. The documentation, such as it is, talks only about how to integrate it with the rest of a built-in fireplace in the design and manufacturing process. But not a word about how you, the end user, might somehow connect the fireplace to any external system. Here you can see the controller:

What you find, if you poke around inside the fireplace, is that from this controller, there are cables that go to all of the places that you would expect, including:

- to the gas control valve (for operating the main gas valve and the pilot gas valve)

- to the halogen bulbs that light up the bed of glass chips

- to the blower that circulates room air through a plenum

- to a radio receiver that receives commands from the remote control

- to a spark igniter

- to an electrode that senses whether the pilot light is burning (kind of like an old-fashioned thermocouple)

- to AC electrical power

One of the connectors is a two-pin connector designated “main on-off switch”. In the fireplace that I was struggling with, this connector simply has a jumper across the two pins.

So one of the first things I explored is whether maybe I could put a relay across these pins, and control the relay with the home automation system. Close but no cigar. If you use the remote control to turn “everything on” meaning the gas flame and the circulating air and the halogen lighting, and if you then open the connection between the two pins of the “main on-off switch”, this only turns the flame on and off. It does nothing to turn the circulating air off or turn the halogen lighting off.

There came a point where I considered putting in a three-pole double-throw relay. A first pole would connect to the “main on-off switch” pins, to turn the flame on and off. A second pole would be able to interrupt power to the halogen lights. A third pole would be able to interrupt power to the air blower. But this all seemed a bit like using a sledge hammer to do what a fly swatter does. And this is a gas flame we are playing with. What if somehow I interfered (unwittingly) with the normal safety design aspects of this controller and its relationship with the gas valve?

Eventually sort of by accident I stumbled upon a $99 product called the Bond Bridge (photo at right, link). The maker of this product says you can use this device to “add wi-fi to ceiling fans, fireplaces and Somfy shades.” It claims to “work with Alexa, Google Home, and SmartThings.” It says it provides “remote control via a Bond Home app” that “works with iPhone or Android.”

So I tried it. But it turns out that the people at the Bond company who tried to figure out how to get their bridge to talk to SIT remote control fireplaces gave up. Here is what I received in a tech support email message from a Bond tech support person:

If your remote is similar to the image above, unfortunately, the remote is not yet supported by Bond. Based on the update that we received, the codes of the remote are complicated and the Bond could not replicate the other functions and capabilities of the remote. We cannot guarantee you that it will work and we have no information if this remote will be tested again or supported any time soon.

They suggested I return the Bond Bridge for a full refund, so that is what I did.

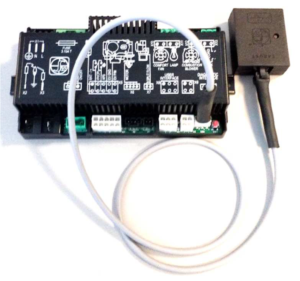

After a lot of clicking around on the Internet, I stumbled upon a product made by SIT called the “Proflame wifi dongle”. This device plugs into a four-pin port on the controller that is labeled as “diagnostic interface”.

The documentation, such as it is, for this dongle sort of hints around that it will only work with certain versions of controller, namely controllers with green writing on them. The one in the photograph has white writing, and the controller in the fireplace that I was struggling with has white writing. Another bit of documentation says the dongle will only work with a controller with a certain firmware version, and I was able to work out that the controller in the fireplace that I was struggling with had a version number that was numerically much smaller.

This wifi dongle made by SIT is very close to being unobtainium. Most web sites offering replacement parts for fireplaces list this dongle as “out of stock” and the controller with the desired firmware version is likewise out of stock everywhere. There were only two vendors that supposedly could ship this dongle, and each priced it at $234. The retail prices for the controller tend to be $600 to $800.

It was with some difficulty that I was able to work out the radio frequency upon which this remote control sends commands to the fireplace. The answer turns out to be 315 MHz.

The solution for connecting the fireplace to home automation turns out to be available on Aliexpress for $12.38, a price that includes shipping from China. It is a Tuya Smart RF (radio frequency) IR (infrared) wifi bridge (shopping cart link). As you can see from the advertising image at right, this marvel permits infrared control of “water”. (I must admit that until now I had not been aware that water is controllable by infrared signals.) As you can see, one of the radio frequencies at which it can transmit RF commands is 315 MHz which is the frequency needed to talk to this fireplace (and, apparently, all models of fireplace). Among the devices it says it can control using RF are “shutter device” and “rice cooker” and “laundry rack”.

By putting this device into “learn mode” and clicking around on the remote control that came with the fireplace, I was able to get it to learn the RF commands for “fireplace on” and “fireplace off”. This turns everything on and off — the flame, the blower, and the lights. If I use this to turn the fireplace on, it powers up with the flame and blower and lights set at whatever levels they were at when the fireplace was previously turned off. (What this means is that if the user wishes to adjust the flame height or blower speed or dimming of lights, this must still be done using the original remote control.)

Basically what is going on is that this $12.38 device from China is able to mimic some of the RF transmissions of the original remote control. The fireplace receives a signal that asks the fireplace “please turn yourself on” and the fireplace complies, by turning itself on. So far as the fireplace knew, this signal apparently came from the original remote control. Instead, this signal came from the $12.38 device. Then it is similar with turning the fireplace off. The fireplace turns itself off having been faked out by the $12.38 device which essentially tricked the fireplace into thinking that somebody had tapped the “power off” button on the original remote control.

I also found that it was a straightforward matter to connect this $12.38 device with a voice assistant such as Alexa or Google Home. So now I can say “Alexa please turn on the fireplace” and Alexa will say “okay” and the fireplace will turn on. I can say “Alexa please turn the fireplace off” and Alexa will say “okay” and the fireplace will turn off.

Let’s talk through what this all adds up to. When I say “Alexa please turn on the fireplace”, what happens is the $12.38 device sends an RF signal to the fireplace to tell it to turn on. Importantly, that complicated controller that appears in a photo above then goes through its entire power-up gas-on procedure. There is some sort of blower activity to blow any unburned gas (from some previous unsuccessful power-on cycle, perhaps) out the flue, or at least to dilute any unburned gas a lot. Then the pilot light gets some gas flow and a spark gap clicks to try to light the pilot light. A second electrode nearby to the flame of the pilot light tests for the conductivity of the gases nearby to that electrode, as a way of working out whether or not the pilot light actually did get lit and stayed lit. Then after a little while the gas valve opens to permit gas to flow into the main burner area. This gas eventually gets set on fire by the pilot light and a sort of curtain of flame pops into view. This flame curtain starts on the left (where the pilot light is located) and travels across the field of view to the right.

My point here is that the safety steps that the controller carries out in an effort to minimize release of unburned gas into the room … all of those steps get carried out in the same way regardless of whether the “please turn yourself on” command came from the original remote control or came from the $12.38 device. There is no compromise of safety in this “integrated with home automation” approach.