Maybe you have bufferbloat, perhaps not being directly aware of it. In a local area network (LAN) suffering from bufferbloat, the network can become practically unusable for many interactive applications like voice over IP (VoIP), media streaming, online gaming, and even ordinary web browsing. This can happen no matter how much money you spend to get high-speed service from your ISP (internet service provider).

If you have bufferbloat, then the thing to do is to take the protective measure of installing and using SQM (“Smart Queue Management”) in your data router. It might turn out that your data router is unable to do SQM in which case you might want to upgrade your router.

How can you figure out whether you have bufferbloat? How can you fix it?

This blog article talks about these things.

In the early days of the Internet, you were lucky if you could get a (dialup modem) connection with your ISP of 56K bits per second. In those days, to the extent that there might be a bottleneck between your computer and a distant server, almost certainly the bottleneck was the connection to the ISP. When I moved my patent law firm from Manhattan to the mountains of Colorado back in the 1990s, we felt extremely blessed to have picked a location for our new office that could use a frame relay data connection to our ISP at the then-luxurious speed of 772K bits per second (half the speed of a T1 data line). Again to the extent that there might be a bottleneck between our computer and a distant server, almost certainly the bottleneck was the frame relay connection to the ISP. In those old days there was no such thing as VOIP (voice over IP), nobody tried to stream video, and nobody tried to play data-intensive video games that would interact with players at other locations. In those old days, if you were to count up the entire number of internet-connected devices in your home or office, it might be one or at most two devices per person. In those old days, it was rare to try to do anything more data-intensive than checking email and visiting web sites.

Decades have passed and by now it is commonplace for ISPs to offer speeds that are much faster than in the old days. It is commonplace for a cable TV ISP to deliver a download speed of 300Mbps or even a gigabit per second, with an (asymmetric) upload speed of 30Mbps. A user served by optical fiber might have symmetric upload and download gigabit speeds.

But a first thing that has also happened as these decades have passed is that the number of internet-connected devices in your home or office might be a dozen or more internet-connected devices per person. In my own home, for example, at the present moment there are over one hundred outstanding DHCP leases. My Home Assistant system has over one thousand “entities”, each of which from time to time needs to send or receive the occasional data packet.

A second thing that has happened as these decades have passed is that we now routinely do things that consume astonishingly bigger amounts of Internet data than in the old days. We click to watch a movie in UHD (ultra high definition) and in the span of an hour or two, we consume one million times more data than we would have consumed in an entire month (in the old days). We join a video conference on Gotomeeting or Teams or Zoom, and both directions (upload and download) require tens of millions of bits per second for a good connection. In today’s work-from-home world we connect to work on a VPN and when we save a massive data file to a server at work, we chafe if it takes more than a few seconds.

Which now brings us to “bufferbloat”. It turns out that now, in the year 2025, when something that relies on the Internet does not work the way we expect, the culprit is unlikely to be the connection to the ISP. The bottleneck is, instead, likely to be inside the data router in our home or office. The name given to this problem inside the data router is “bufferbloat”.

What exactly is “bufferbloat”? You can read the Wikipedia article. In geek terms, bufferbloat is the undesirable latency that comes from a router or other network equipment buffering too many data packets. Perhaps the best way to understand bufferbloat is to watch the episode of I Love Lucy that aired on September 12, 1952 entitled Job Switching (excerpt on Youtube). In the episode, Lucy and Ethel realize that they are having trouble keeping up with a stream of chocolates along a factory production line. Eventually they try to deal with the problem by setting some chocolates aside, off the production line, presumably with a goal of dealing with those set-aside chocolates later. Using the terminology of today’s data routers, Lucy and Ethel were “buffering” the chocolates. (They also try to get rid of some of the chocolates by eating them.)

How do you know if you have bufferbloat? It turns out that this is an objectively measurable thing. Start by finding an ethernet cable and connecting your computer to the Internet using ethernet. Turn off your wifi adapter (which might be called “going into airplane mode”). Momentarily turn off any bandwidth-heavy tasks on your network. Then go to this Bufferbloat and Internet Speed Test and click “start test”.

(Another way to test for bufferbloat is to carry out whatever traditional speed test you already know and love, while arranging for several other data-intensive tasks to be going on at the same time. If the speed test results are nowhere close to the speeds that you are paying for with your ISP, then this might mean you have bufferbloat.)

The Bufferbloat and Internet Speed Test will measure your “latency” (ping time to a distant server) under conditions of low data usage. This test will then repeat the latency measurement at a time when a big data download is taking place. Finally, this test will repeat the latency measurement at a time when a big data upload is taking place. If latency gets worse during the download or the upload, then very likely the culprit is bufferbloat.

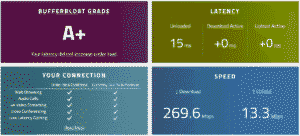

The first time I ran this test in my home, the test gave me a “C” grade. This meant that I very likely had quite a bit of bufferbloat going on.

How does one get rid of bufferbloat? In the I Love Lucy episode, common sense tells us that the only way to deal with the speed of the production line would be to add workers running in parallel with Lucy and Ethel, or somehow find workers who could work twice as fast (if indeed such workers could be found).

Many ISPs try very hard to convince you to rent your data router from the ISP. I am not aware of any rental router provided by any ISP that supports SQM. I strongly suggest not using a router that is provided by your ISP for this reason, and also because the firmware in the router is proprietary. (As discussed below, when a router uses proprietary firmware, there is no way for you to know whether the firmware contains backdoors or has security flaws.)

It might be thought that bufferbloat could be cured by giving more money to your ISP to get faster upload and download speeds. But it is very unlikely that giving more money to your ISP will cure bufferbloat if you suffer from it.

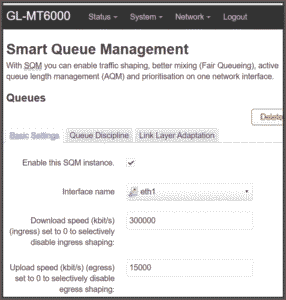

Start using SQM in your existing router. It might turn out that your existing router already has the ability to do SQM (smart queue management). If so, turn it on and see if the bufferbloat goes away.

Or it might turn out that your existing router lacks SQM software but will permit you to install SQM software in the router. If so, install SQM, turn it on, and see if the bufferbloat goes away.

In my case, I added SQM software to my existing router and turned it on and repeated the bufferbloat test. My grade improved from a C to a B. The bufferbloat was less bad, but still not eliminated.

My existing router was a Brume 2 (seen at right), which is powered by a MediaTek MT7981B dual-core processor clocked at 1.3GHz. Even using SQM, its two cores running at 1.3GHz were not able to keep up with the (metaphorical) stream of chocolates coming along the production line.

Upgrade your router. I upgraded to a Flint 2, which is powered by a quad-core processor clocked at 2GHz. Doubling the number of cores might be analogized to adding two more workers running in parallel with Lucy and Ethel, while increasing the clock speed from 1.3GHz to 2GHz might be compared with asking all of the workers to drink a lot of Diet Mountain Dew (which is highly caffeinated) before starting their work shift.

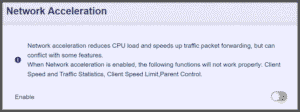

The Flint 2 has an optional hardware feature called “network acceleration” which has a goal of reducing CPU load and speeding up traffic packet forwarding. But even with that feature turned on, my bufferbloat grade did not reach an “A”. (The previous Brume 2 also had this feature, but it likewise did not overcome the bufferbloat.)

The Flint 2 does, fortunately, does permit the user to install SQM software in it. I did so, and I turned on SQM (screen shot at right). (I also turned off the network acceleration, because it can work at cross purposes with the SQM.) I repeated the test, and you can see the results at the top of this article. Yes, I got an A+ grade.

Other routers that support SQM. The web page that provides the Bufferbloat and Internet Speed Test lists and links to four suggestions for routers that support SQM. They are:

-

- Amazon eero Pro 6 mesh WiFi router

- NETGEAR Nighthawk Pro Gaming 6-Stream WiFi 6 Router

- IQrouter – IQRV3 Self-Optimizing Router with Dual Band WiFi

- Ubiquiti EdgeRouter 4

(The provider of this test acknowledges that the links are affiliate links, and discloses that it makes a small referral fee from Amazon for each purchase, which helps the provider to cover hosting costs.)

I avoided any of those four routers, for the simple reason that they use proprietary firmware. You have no way to know whether some backdoor might have been hidden in the router. You have no way to know whether the firmware has security flaws.

In contrast, the Brume 2 and Flint 2 routers use open-source OpenWRT software. If anybody had ever hidden a backdoor in that software, one or another of the hundreds of volunteer coders would likely have noticed it. The volunteer coders have a goal of keeping abreast of best coding practices and firmware updates happen as needed, to minimize security flaws.

Do you have bufferbloat? Have you fixed it? Did you use SQM to fix it? Please post a comment below.