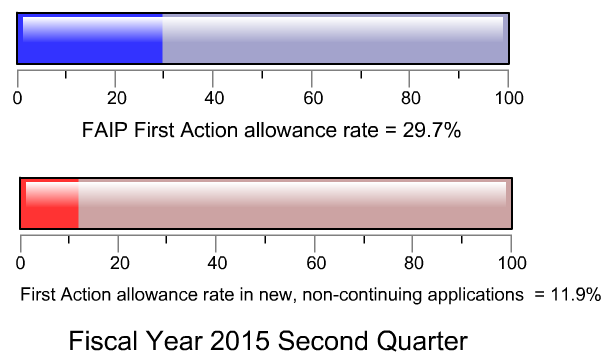

The First Action Interview Pilot program (FAIP) is a way to try to get a patent faster. For some applicants it may be smart to use FAIP. USPTO’s patent dashboard claims that the first office action allowance rate for FAIP cases is 30%, while the corresponding statistic for non-FAIP cases is 12%. This suggests that an applicant might be smart to try FAIP. In this blog post I will discuss some of the potential advantages and disadvantages of FAIP.

USPTO’s patent dashboard claims that the first office action allowance rate for FAIP cases is 30%, while the corresponding statistic for non-FAIP cases is 12%. This suggests that an applicant might be smart to try FAIP. In this blog post I will discuss some of the potential advantages and disadvantages of FAIP.

When I was first in practice, the MPEP had a section stating that the applicant should never seek to communicate with the Examiner on an application until the Examiner had mailed a first Office Action. In many ways this provision of the MPEP made sense. An Examiner will take up one case at a time, and if Examiners were constantly being asked to look at some other case than the case the Examiner is examining right now, the result would be a loss of efficiency with the Examiner constantly having to change gears.

As far as I can see, that section of the MPEP is gone now. But the concept is still valid — generally it is not doing anyone any favors for an applicant to pester an Examiner about a case that the Examiner has not yet reviewed.

The general idea of FAIP is that the applicant asks nicely for an opportunity to communicate with the Examiner earlier than the first Office Action. Basically it is a way of signaling to the Examiner that you would be delighted if the Examiner were to pick up the phone and call you after the Examiner has had an opportunity to look at the application. As you can see from the USPTO dashboard image quoted above, some thirty percent of the time this phone call from the Examiner leads to an allowed case!

FAIP does come with strings attached. The chief potential drawback for FAIP is that the applicant must promise in advance not to traverse any restriction requirement, no matter how unreasonable it might be. The applicant must also cancel any total claims beyond twenty and any independent claims beyond three, and must eliminate any MDCs (multiple dependent claims).

Gaming system not permitted. There is a rule that says that if an application has not yet received an Office Action, the applicant may, if it wishes, withdraw the application and receive a refund of the search fee and any excess-claims fees. The way it is supposed to work with this abandon-and-get-your-fees-back rule is that you don’t know yet whether or not the Examiner will say it is patentable. It’s as if you had asked for a refund on your lottery ticket at a time when you had not yet scratched it off to see if it was a winning ticket. It would be unsportsmanlike for an applicant to sign up for FAIP and then get a sneak peak as to patentability by means of FAIP and then abandon the application and ask for the refund of fees. It would be like scratching off a lottery ticket, finding out that it is not a winner, and only then asking for a refund. So it makes sense that to use FAIP, the applicant must promise not to “game the system” in this way.

As a matter of expectations management, it is important to keep in mind what you do not get with FAIP. Unlike, say, PPH or Track I, the FAIP program does not obligate the Examiner to take up the case for examination any earlier than would ordinarily occur. If FAIP were to get you a patent faster, it is not because the first Office Action arrives sooner. It is because (hopefully) you get your Notice of Allowance around the time of the first Office Action rather than after some subsequent Office Action.

Suppose you have filed an application or you are thinking of filing an application. How should you go about choosing whether to make use of FAIP?

I’d guess that for most of the recently filed by our firm, the cases did not have more than twenty total claims. And did not have more than three independent claims. And did not have any MDCs. So for those cases, the “strings attached” relating to claim count and MDCs would not have been a reason to hold back from making use of FAIP.

We have, however, run into quite a few unreasonable Restriction Requirements in recent years. We would need to think twice before handing the Examiner a carte blanche to be even more unreasonable about Restriction Requirements.

But sometimes you can sort of guess by looking at a case that it is not particularly likely to fall victim to an unreasonable Restriction Requirement. If you were to have such a case, and if you already fell within the three-and-twenty-and-no-MDCs boundary, then it might make good sense to make use of FAIP.

How do you do it? It’s pretty easy. Basically you fill out USPTO Form PTO/SB/314C and use it as a checklist. Knock down your claim count if needed, file the form, and wait for the telephone to ring with a call from the Examiner.

This blog article opens with USPTO’s claim in its dashboard that the first-office-action-allowance rate for FAIP cases is more than double (in percentage terms) the FOAA rate for non-FAIP cases. I do find that claim plausible. What the dashboard does not say is whether the allowance rate over the pendency of the case is higher for FAIP cases than for non-FAIP cases. Of course, if your FAIP case is one of those 30% that got allowed on first office action, then there is no second or third office action to speculate about that might or might not have led to an allowance.

It is possible to double-dip. You could, for example, put a case on the PPH and file the FAIP form. That would accelerate the first office action (because of the PPH) and would give you the potential benefits of that early interview.

What exactly is the explanation for why FAIP works? Does it really make a case more likely to get allowed that it has 20 claims rather than 21? Surely not. Does the promise not to traverse a Restriction Requirement somehow make it more patentable? Surely not. I think there are several factors that tend to explain why FAIP works.

The first is that the mere filing of the FAIP document is a signal to the Examiner that you are willing to talk turkey. Normally an Examiner who picks up a case has no idea whether the applicant (or applicant’s representative) will do anything at all to help the Examiner reach a disposition of the case. The Examiner has no idea whether it would be a good use of time to pick up the phone and call up the applicant. But a case that contains an FAIP document is a case where the Examiner knows that there is someone at the other end of the telephone line who is prepared to try to cooperate.

Another factor is that an applicant probably does not file an FAIP document in a case that the applicant knows was drafted poorly, or that the applicant knows is a bit of a shot in the dark so far as patentability is concerned. If an applicant looks over its portfolio of pending cases, looking to see which one is deserving of an FAIP document, probably the applicant is going to pick out a case that seems at least somewhat likely to have patentable subject matter in it, and that was drafted fairly well. This self-selection process would help to explain why an Examiner might find that a first office action allowance is possible.

This is sort of like the exuberantly colored tail feathers of the peacock. Scientists tell us that the peacock uses this to signal to a potential mate that he is healthy and has had regular meals recently. The FAIP document in the file is like a nicely colored tail feather, signaling in a vague sort of way that likely as not the application itself may have come from an applicant who actually invented something that is patentable, or at least an applicant that was sophisticated enough to hire a patent practitioner who was sophisticated enough to think of making use of FAIP.

Have you used FAIP? How did it work for you? What reasons might you have for using or not using FAIP? Please post a comment.

Would this work in an RCE or CON where you and the Examiner are almost on the same page but did not get an allowance in the parent? Filing the FAIP may be a good way to remind the Examiner about your newly filed RCE or CON and hopefully speed things up a bit.

Oops. I see that it must be used for a “new” application only so perhaps RCE is out of the question but maybe it would work for a CON or CIP?

Applicant is entitled for an interview before first OA in any continuing application, as a matter of right. You’re not required to file a request under FAIP for any continuing application.

Might anyone have an answer regarding the First Action Interview Pilot Program and RCEs?