Over the course of many decades I have loosened and tightened motor vehicle lug nuts hundreds of times. I have always done this with hand tools.

Now I have a big cordless ½-inch drive impact wrench and maybe now I will not be stuck having to use hand tools for lug nuts.

All of a sudden I have no choice but to think about “torque sticks”. Maybe you have strong feelings about torque sticks, in which case please post a comment below. Maybe you have never heard of torque sticks. Loyal readers know exactly where this is going. What follows is a prolonged discussion of torque sticks as they related to big cordless ½-inch drive impact wrenches.

We start with some background. When I was a teenager, I maintained my 1966 VW bug. I had a lug-nut wrench shaped like an enormous X. Whenever I needed to remove or replace a wheel, I used that wrench to loosen or tighten the lug nuts. When tightening the lug nuts, I simply leaned on the wrench until it seemed the lug nuts were “tight enough”. There was no exactitude or subtlety to the tightening process. (I am waiting for someone to slap the buzzer and point out that on a 1966 VW bug, the wheels were actually held on with lug bolts, not lug nuts. Yes you are right, but for this article I will sort of assume that all wheels are held in place by lug nuts, for convenient discussion.)

At some point during my high school years I somehow learned that people who know what they are doing will use a torque wrench to tighten lug nuts. It turns out that everybody except me already knew that this is a “Goldilocks” thing. You don’t want your lug nuts to be too loose, but you also don’t want your lug nuts to be too tight.

Too loose. This is the easy part to figure out. If the lug nuts (or even one of your many lug nuts) were to be too loose, the lug nut might fall off the car and eventually the wheel might fall off.

Too tight. This is the part that everybody else except me already knew. Yes I certainly knew from my own experience that if I were to tighten a lug nut too tight, I would later pay for this by having to use a “breaker bar” to get the lug nut loose again. I might have to put a length of pipe on the breaker bar, to get more leverage. But eventually I caught on that there is another reason why one should avoid tightening a lug nut too tight. If you tighten a lug nut to be too tight, you run the risk of permanently damaging or even breaking the threaded post which holds the lug nut. If the wheel is aluminum or magnesium, then a too-tight lug nut might damage the wheel.

So as it turns out, people who know what they are doing will use a torque wrench to tighten lug nuts. They will look up somewhere to find out the correct torque to which the lug nuts need to be tightened. And having found this extremely important number (in the US, the number of foot-pounds), they will use a torque wrench to tighten each lug nut to that exact torque.

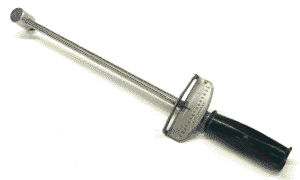

So yes, eventually I scraped together enough money to purchase a beam-type torque wrench. This was a thing of elegant simplicity. A long indicator stayed straight, while the wrench itself (the “beam”) deflected. The arrow pointed to a number and this was the number of foot-pounds of torque.

Importantly, the handle wobbled. It was on a sort of pivot. After a little while I somehow figured out why. The problem is that if the handle were fixed rigidly to the beam, there was a danger that the user’s own grip on the handle might apply a spurious torque to the beam, thus introducing error in the measurement.

Part of the magic of this elegantly simple design is that if it began accurate, it would remain accurate no matter what happened after that. You could drop the wrench or abuse it in almost any way, and it would not lose its accuracy. (The only adjustment that would ever possibly be needed is to bend the indicator so that it points at zero when the tool is at rest.)

Decades passed and by now I think I no longer possess that torque wrench. Recently I purchased a “click” torque wrench. With this wrench, you “dial in” the desired torque. As you tighten the lug nut, eventually the wrench clicks. This tells you that you have achieved the desired torque.

Getting lug nuts loose. As mentioned above, the way most do-it-yourselfers would loosen lug nuts was (and still is) a “breaker bar”, often augmented with a length of metal pipe for leverage.

For decades, the standard tool for professionals for loosening lug nuts was an air-powered ½-inch drive impact wrench. In any well-equipped shop there would be an air compressor and pressure tank, and pipes to distribute compressed air to all locations in the shop. A flexible hose would deliver the compressed air to the ½-inch drive impact wrench. (The January 7, 2009 episode of How It’s Made shows how such wrenches are made.)

I gather that nowadays most shops use cordless ½-inch drive impact wrenches. The cordless ½-inch drive impact wrench is heavier and bigger than its air-powered cousin, but it saves having to wrangle the air hose.

Many brand-name cordless ½-inch drive impact wrenches cost $200 to $300. But if you click around, you can find generic cordless ½-inch drive impact wrenches for as little as $85. The one that I just purchased (for that price) also included two batteries, a charger, and a set of four impact sockets. They also threw in a pair of nonslip gloves, and it all neatly fits into a sturdy carrying case.

With an air-powered wrench, what would sometimes happen when one is loosening a lug nut, the moment that the lug nut would come “loose” would be a moment that the wrench would spin much faster. The now-loose lug nut might get flung away and be hard to find. Which brings us to a really nice feature of most cordless ½-inch drive impact wrenches. When the wrench is set to turn counterclockwise to try to loosen a tight lug nut, a circuit detects the reduced power load from the motor at the moment that the lug nut comes loose. In response, the motor reduces speed, so that the lug nut will not get flung away.

Yes, dear reader, by now you are wondering if and when I will actually somehow come around to the promised topic of torque sticks.

The DIYer who comes into possession of a big ½-inch drive impact wrench is, of course, delighted at the prospect of getting a lug nut loose without having to struggle and struggle with a breaker bar and a length of pipe.

But the next thing that the DIYer realizes is that if the impact wrench can loosen and remove a lug nut, it stands to reason that the impact wrench ought to be able to replace and tighten that same lug nut at some appropriate later time in the process of changing snow tires, for example.

(We are almost there, dear reader.)

Yes it is true that that the impact wrench can go each of two directions — counterclockwise and also clockwise. The reality is, however, that it would be a big mistake to use the clockwise direction without thinking about it enough.

My car has a specified lug-nut torque of 129 foot-pounds. But my spiffy new cordless impact wrench, with its ½-inch drive, is able to develop 885 foot-pounds of torque. I could pull the trigger on this wrench and I could destroy a lug nut or its threaded shaft or an aluminum wheel.

Enter the torque stick. The idea is that if you want, say, 130 foot-pounds of tightening torque onto your lug nuts, you would lay your hands on a torque stick that has the number “130” written on it. You snap the stick onto your big impact wrench, and you snap your impact socket onto the stick. And the idea is that you can pull the trigger on your big impact wrench and tighten the lug nut, and as if by magic, the tightening process would build up neither more nor less than 130 foot-pounds of torque at the lug nut.

How can this possibly work? There are Youtube videos about this and there are detailed articles about this. The theory of operation takes advantage of the way that impact wrenches work.

Inside any impact wrench, what happens is that a spring-loaded hammer gets wound up and repeatedly gets released to smash (in a rotating way) onto an anvil that is on a shaft that drives the impact socket. This happens over and over again, many times per second. As mentioned above, this might develop 885 foot-pounds of torque. (According to the device specs, if you somehow have the self-control to pull the trigger less, you might get 332 foot-pounds or 527 foot-pounds instead of the full 885 foot-pounds.) The impacts might happen 25 times per second, or 42 times per second, or 58 times per second, depending on how you pull the trigger. (It turns out that the state-of-charge of the rechargeable battery will also make a big difference in the torque that gets developed.)

The enormous problem is that no matter how gently you pull the trigger, you are going to risk damaging the nut or threaded stud or wheel, because 332 is also bigger than 129.

The theory of operation for the torque stick is that it “gives”. It is springy, and it resonates with the cycle time by which the hammer repeatedly strikes the anvil. (Or at least it hopefully resonates.) And maybe, if all goes well, the stick absorbs all of the rotational energy of the hammer that happens to exceed the target torque for the lug nut.

Some people use these torque sticks with their air-powered impact wrenches and I am told that sometimes the sticks work (more or less).

Youtube has dozens of videos in which people test this. They use a torque stick until it has (supposedly) tightened a lug nut to a particular torque. They then put a torque wrench onto the lug nut to see if more tightening is needed to reach the desired torque. In nearly all of the videos, the answer is “no”. In plan language this means that there is very little risk of failing to tighten the lug nut enough.

The natural next question is “but does the torque stick tighten the lug nut too much?” And in most of the videos, the answer is “yes”.

The makers of the videos try, as best they can, to see if they can find some pattern or explanation for the undesirable “too tight” result. Some video makers hypothesize that the torque sticks only work well for air-powered wrenches, and maybe only for certain makes and models of air-powered torque wrenches.

The consensus view is that if you want to end up with some target number of foot-pounds on your lug nuts, you should use a torque stuck that is rated at maybe 20% less than the target torque. (This will hopefully tighten the lug nut quite a lot but will hopefully avoid over-tightening it.) Having operated the wrench until the torque stick is “done”, the consensus view is to tighten the lug nut the rest of the way using the same old-fashioned torque wrench that you were using long before you came into possession of the big cordless ½-inch drive impact wrench.

This allows you to save time spinning the lug nuts back into place, while (hopefully) avoiding getting them too tight.

Do you have strong feelings about torque sticks? If so, please post a comment below. Did you find this discussion of torque sticks interesting? If so, please post below.

Fascinating. I didn’t know they made torque sticks.

I have scars on my knuckles and had sore feet from jumping up and down on my lug wrench when changing a tires on my trusty ’68 & ’73 Bugs.

Alas, now I just use the AAA.