For decades I have struggled with the many competing and proprietary ecosystems for the many types of home automation devices in my house. Each ecosystem has its own proprietary app, one for lighting, another for window shades, yet another for thermostats, and so on. This means, for example, that if you first get the idea to turn a light on or off, you must remember which app is the correct one for lighting, open that app, log in, and turn the light on or off. If you next get the idea to raise or lower a shade, you must remember which app is the correct one for shades, open that app, log in, and raise or lower the shade.

For decades I have struggled with the many competing and proprietary ecosystems for the many types of home automation devices in my house. Each ecosystem has its own proprietary app, one for lighting, another for window shades, yet another for thermostats, and so on. This means, for example, that if you first get the idea to turn a light on or off, you must remember which app is the correct one for lighting, open that app, log in, and turn the light on or off. If you next get the idea to raise or lower a shade, you must remember which app is the correct one for shades, open that app, log in, and raise or lower the shade.

In recent days I have migrated my house to Home Assistant, and now I can open a single app and it will cover any and all of these things. Not only that, but I am delighted to find that Home Assistant (“HA”) is free and open-source software, and is designed from the ground up with the homeowner’s privacy in mind.

What got me started on all of this was a project that had been on my to-do list for several years. I wanted to be able to press one button, just one. And this single button press would accomplish all of the following:

-

- adjust window shades to darken the room where a big-screen television gets watched;

- turn off any nearby lights that might be “on” that do not need to be “on” during TV viewing;

- turn on a couple of subtle nearby lights, with the dimmer set to only about 10%, for a bit of background lighting;

- turn on the TV; and

- turn on the receiver that provides Dolby 5.1 surround sound in the TV room.

The alert reader will already know where this is going. Of course what you will now hear from me is that this turned out to be extremely difficult to accomplish, sucking up two lost weekends of my life.

A starting point was to resume an experiment that I had begun a few years ago, namely an effort to gain some familiarity with Flic buttons, one of which is shown at right with a 9-volt battery to show scale. The idea of a Flic button is that you press the button, and somehow Alexa learns that you want something to happen, and Alexa then makes it happen. (I don’t give full credit here to the versatility of Flic. You can set it up so that Flic sends a request to any of about four dozen places, of which Alexa is only one.)

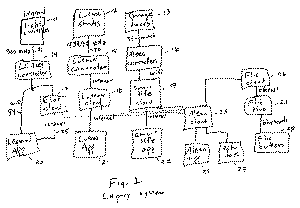

Flic buttons have been around for ten years now, but I only got a clue about them about four years ago. I purchased a Flic system (three buttons and a hub) and played with it a bit, then saw something shiny and moved on to other projects. But a couple of weeks ago I resumed this project. I set it up so that (hopefully) my press of the Flic button would do the five things listed above. Figure 1 shows, in functional-blog diagram form, the system that was intended to make this happen. (I suggest printing out Figures 1 and 2 so that you can refer to them in the paragraphs that follow.)

The idea is that I would press a Flic button 28, which would send a Bluetooth message to a Flic hub 27, which would send a request to the Flic cloud 26, which would send the request to the Alexa cloud 23. The Alexa cloud would then carry out a “routine”, which sends messages to a number of additional clouds 17, 18, and 19 in the figure. Each of these clouds would then pass a message to a corresponding hub or controller 14, 15, 16 located in my house. Each of those hubs and controllers would then pass messages for the last 50 feet, to a number of window shades, a number of light switches and dimmers, a television, and an audiovisual receiver.

Except of course not. What should have been a few moments of clicking around in my Alexa app 24 ended up as two lost weekends, as detailed in this article.

The first disappointment was to learn that the Eliot cloud 17, provided by Legrand, which is the maker of my expensive light switches and dimmers 11, is in disrepair. As described in this blog article, Legrand has abandoned the hundreds of thousands of homeowners who have each spent thousands of dollars purchasing Legrand smart light switches and dimmers. What this meant in very practical terms was that to accomplish my goal (one simple button press makes five simple things happen), I had to somehow eliminate Eliot cloud 17 from my world and find some other way to pass messages to my Legrand light switches.

The first disappointment was to learn that the Eliot cloud 17, provided by Legrand, which is the maker of my expensive light switches and dimmers 11, is in disrepair. As described in this blog article, Legrand has abandoned the hundreds of thousands of homeowners who have each spent thousands of dollars purchasing Legrand smart light switches and dimmers. What this meant in very practical terms was that to accomplish my goal (one simple button press makes five simple things happen), I had to somehow eliminate Eliot cloud 17 from my world and find some other way to pass messages to my Legrand light switches.

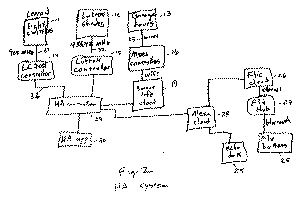

Somehow I got the idea to try to use Home Assistant. Home Assistant (“HA”) is a free and open-source automation assistant for the home. As may be seen in Fig. 2 below, what I did was to purchase a Raspberry Pi 5 computer (about $120), and I loaded the free and open-source HA software into the Raspberry Pi.

You can see the Raspberry Pi 5 computer here:

(The 9-volt battery is in the picture just for scale, to appreciate the diminutive form factor of the Raspberry Pi 5 computer.)

This HA path is not for the faint of heart. One must have some measure of tech-savviness and persistence to migrate over all of the various ecosystems in the house so that they learn how to communicate with the new HA controller (item 29 in Fig. 2). It was easy to do this for the Lutron devices 12 and 15. It was easy to do this for the garage-door devices 13 and 16. It was easy to do this for the smart thermostats and for several other systems in the house. But it was quite a challenge to get this to work for the Legrand light switches 11 and controller 14. You can read about this challenge, and the happy outcome, in this blog article.

As time goes on, all of the “last 50 feet” links such as 31, 32 and 33 will hopefully eventually get replaced by links according to a new open standard called “Matter“, see my blog article. This new open standard should also eventually reduce the number of hubs and controllers such as 14, 15, and 16 to a single Matter controller, as I discuss in the blog article.

Now, with the HA migration largely accomplished, it is indeed the case that with a single button press, I get all of the following:

-

- adjust window shades to darken the room where a big-screen television gets watched;

- turn off any nearby lights that might be “on” that do not need to be “on” during TV viewing;

- turn on a couple of subtle nearby lights, with the dimmer set to only about 10%, for a bit of background lighting;

- turn on the TV; and

- turn on the receiver that provides Dolby 5.1 surround sound in the TV room.

There are other payoffs from this migration of the various house systems to HA. A first payoff is that with a single smart phone app 30, I am able to control everything in the house. (The previous situation was that I had to juggle a dozen proprietary apps on my phone.)

A second payoff is that the HA system was designed from the outset to pay attention to privacy. Very little information gets communicated or stored anywhere outside of the house. I am delighted to see that the HA group is beta-testing an “HA voice assistant” that is intended to do much of what an Echo Dot or Google Home smart speaker would do, with all of the voice processing taking place inside the user’s house.

If you wish to post a comment on this article, please do so here.