I am told that not very many applicants make use of the two Collaborative Search Pilot (CSP) programs at the USPTO. Each of the programs offers a fast-track way to get a strong patent. The more I think about CSP, the more I wonder why the programs get such little use. In this blog article I will describe the programs and I will offer my thoughts as to how an applicant might go about deciding whether or not to make use of the programs. Finally I will mention the actual numbers of times the two CSP programs have gotten used by applicants.

First, I’ll briefly describe how the CSP programs work. Then I will point out how the outcome is a stronger patent than you would otherwise get. Finally I will talk about factors that might influence an applicant’s decision process as to whether or not to make use of CSP.

How the CSP programs work. With CSP, you file a the same patent application in two patent offices. There are two CSP programs, and each is a pilot program expiring October 31, 2020. One program is a bilateral program between USPTO and JPO (the Japanese Patent Office). The other program is a bilateral program between USPTO and KIPO (the Korean Intellectual Property Office). So this means you file the same patent application in USPTO and JPO, or the same patent application in USPTO and KIPO.

With each patent application you file a request for participation in CSP.

One consequence of the fact that you filed a CSP request is that each Office puts the application momentarily “on hold” rather than mailing out an Office Action right away. And the two Offices coordinate with each other to reach an agreement that yes, the applications in the two Offices will be handled in a coordinated way.

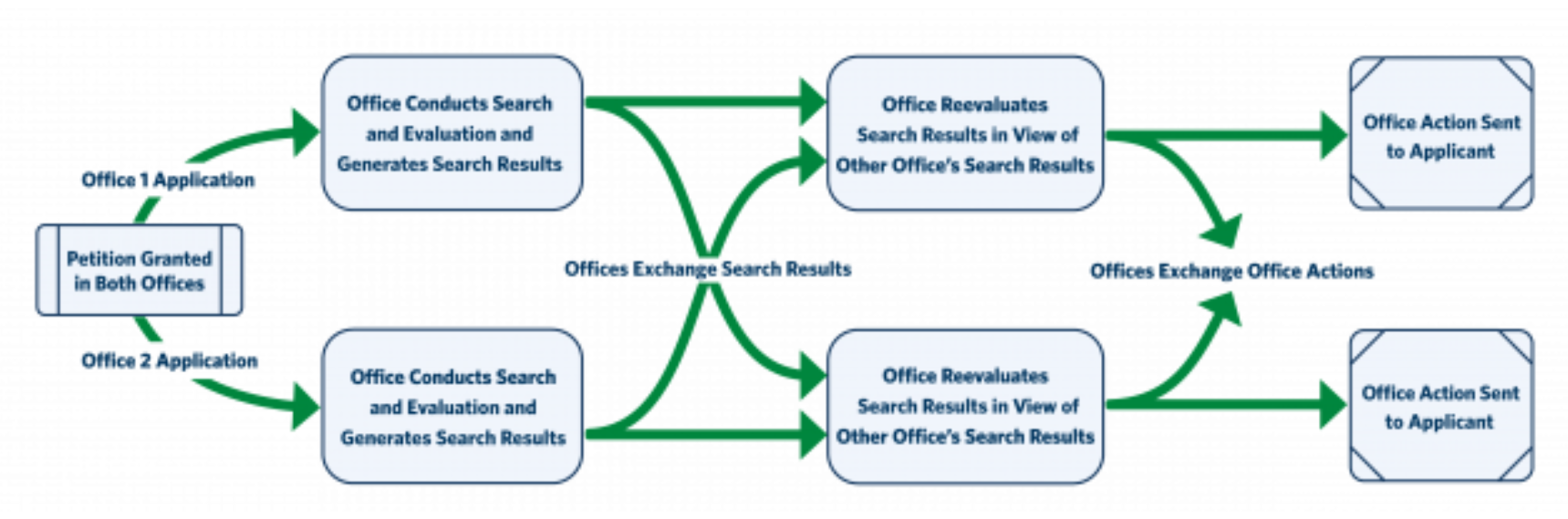

You can then look at the flow diagram reproduced above. The two Offices each put their respective application to the front of the line to be examined. (In the USPTO this means the application is even more special than “special”.) Each Office carries out a search. The Offices swap their search results according to a coordinated and fast timetable. Each Office then carries out an examination, taking into account all of the search results that were found in both Offices. The Offices swap their examination results according to a coordinated and fast timetable.

(You would hope that part of this program is that the US Examiner would cite all of the JPO or KIPO search results on Form 892, so as to save the applicant having to do so. And I am delighted to tell you that yes, in CSP the US Examiner does exactly that.)

The Offices then mail out Office Actions. Assuming that patentable subject matter is found, the applicant can pay issue fees in one or both Offices and obtain granted patents in one or both Offices.

A stronger patent. Imagine that you are counsel representing the patent owner in court, and imagine that the patent came from this CSP program. Of course the accused infringer will try to convince the judge and jury that the patent is invalid — that supposedly it should never have been granted. Here is the kind of thing you can say:

Ladies and gentlemen, you have heard my learned opponent invite you to consider whether perhaps this patent should never have been granted because of prior art that was overlooked. But you might be interested to know that during the time that this patent application was pending, prior art searching was carried out by not one, but two patent offices. The Examiners in these patent offices were fluent in the English and [Japanese or Korean] languages. Before the claims were found to be patentable, these Examiners shared with each other the prior art that they found. The Examiners from these two patent offices shared their thoughts as to whether the claims were patentable in view of the prior art that was found. Only after all of these things took place did the patent office decide to grant a patent. And this is the patent before you now.

This sounds a bit like the “super patent” that I have blogged about. With a super patent, the number of participating Offices is five. With CSP the number of participating Offices is two. With either program, you have a number (either five or two) that is bigger than the “one” that you have if you follow ordinary patent prosecution in a single patent office.

Common sense tells you that if you obtain a Notice of Allowance in a CSP case, your granted patent will be stronger than if it had not been in CSP.

How to decide. How might an applicant decide whether or not to make use of CSP? I can think of a number of factors that might influence such a decision.

- Timing of expenditure. The purchase price of the lottery ticket that is a CSP filing project is, roughly, the cost of a US filing added to the cost of a Japanese or Korean filing. This may include the expenditure to translate the patent application from English into the foreign language. Of course it includes a round of government fees and a round of local professional fees in each country. As a timing matter, this money is being spent at a time when the applicant probably does not yet know whether or not the invention is patentable. If it later turns out the invention is not patentable, or if the invention loses its business value some time after the double filing has taken place, then the money has been spent and is gone.

- Filing path includes these particular Offices? Clearly this program makes the most sense for an applicant that already knows, very early in the filing process, that it is going to want to file applications in both target Offices (both US and JPO or US and KIPO). If on the other hand the applicant’s past state of mind has been to wait until (say) the 30 months of PCT to decide whether or not to spend the money for a JPO filing or for a KIPO filing, then the applicant may have less of a taste for CSP.

- Preference for avoiding issued cases in which one wishes one could have filed an IDS. A scenario that often arises for an applicant that somehow obtains a quick US patent (perhaps through Track I) and later receives search results in a non-US patent office is that the applicant regrets the fact that now it is not possible to file an IDS in the US case to get the references from the non-US patent office considered in the US case. With CSP, if for example you know that the two Offices in which you were going to file are US and JPO, then you could use CSP in those two Offices and you can be quite sure that each Office will be fully aware of all of the search results from the other of the two Offices.

- Desire to Get Patents Fast. CSP is one of the ways to get a patent fast. Yes, there are also other ways, among them PPH, Track I, and Rule 496. But the applicant that wants to make smart decisions about choosing a filing path needs to be aware of all of the tools in the toolbox, one of which is CSP. I am told that with CSP it is commonplace that the applicant knows whether or not it is going to get a patent (in two different Offices!) in as little as 8-9 months after filing.

- Desire to Get Patents Fast without having to spend extra money. Some filing paths that have a goal of Getting a Patent Fast cost extra money. Track I, for example, costs an extra $4000 (for a large entity). CSP, on the other hand, costs nothing extra beyond the money that the applicant would already have spent simply to file the two underlying patent applications.

- Desire to get a strong patent. As discussed above, a patent that has been granted after passing through the CSP process will be stronger TYFNIL than a patent that has not. An applicant desiring to get a strong patent will want to consider the use of CSP.

- Comfortable with claim number limits. To participate in CSP the application is limited to 3 independent claims and 20 total claims, and is not permitted to use multiple dependent claims.

- Comfortable with promising not to traverse. To participate in CSP the applicant is required to promise in advance not to traverse any restriction requirement. On a practical level this means the applicant needs to draft the claims in a way that makes clear that only one invention is being claimed.

- Comfortable with paperwork and procedural requirements for filing. The CSP requires the applicant to juggle several timing issues, including getting the case into the CSP program in each of the two Offices involved chronologically before either of the two Offices has taken up its application to be examined. The applicant must make sure that at least the independent claims correspond between the two applications. To make all of this work, the alert applicant will likely want to file the applications within just a few weeks of each other rather than separating them by the 12 months that often happens in legacy Paris Convention filings. The DAS system will be an ideal way to perfect a priority claim between the two Offices.

The actual levels of usage. Can you guess how many times these two CSP programs have actually gotten used by applicants? These two programs were launched on October 1, 2017 (the start of a fiscal year) meaning that by now, each program has been running for a bit more than two years. Each program was designed to be able to accommodate as many as 400 petitions per fiscal year. This means that during the two fiscal years ending September 30, 2019, there might have been as many as 800 petitions handled for the US-KR CSP and another 800 petitions handled for the US-JP CSP. Had this level of participation been reached, then there might have been some potential users of the CSP who would be turned away.

The actual result, if I have understood the USPTO web site correctly, is that over the past two years instead of as many as 800 petitions being filed for the CSP between USPTO and KIPO, what actually happened is that only 170 petitions got filed. Turning to the CSP between USPTO and JPO, instead of as many as 800 petitions being filed, the number of petitions that actually got filed was 54.

In other words, the caps of 400 have not been reached in either of the two programs during either of the past two fiscal years.

I’ll make a guess as to factors helping to explain why the numbers are 54 and 170 instead of 800 and 800.

- Inertia. One factor might simply be inertia. Plenty of filers get into a rut and do their filings along some path and nobody sticks their neck out to try a radically different path.

- Lack of aligned planets. For one of these CSP petitions to get filed, what has to happen is that a lot of planets need to align. The would-be user of CSP from the US has to be an applicant with enough money in their pocket to bankroll a Paris-type Japanese or Korean filing (at a cost of maybe $10K). Instead of deferring this expense for as long as 30 months with PCT, the filer has to be prepared to spend this money even faster than on a 12-month Paris timetable, so as to get petitions filed in both Offices chronologically prior to any Office Action in either Office. The filer has to actually be aware of the CSP program. That last requirement is a bit of a challenge since it is not easy for any office to successfully communicate any particular outreach message to all possible applicants.

Have you considered either of the CSP programs? Have you used either program? Please post a comment below.

Good content (as always). I will definitely discuss using the CSP program(s) with my team.