(See followup article here.)

(See followup article here.)

I wonder how many trademark practitioners around the world noticed when, on November 1, 2019, IP Australia became an Accessing Office in DAS for trademarks? Continue reading “Australia has joined DAS for trademarks”

Bluesky: @oppedahl.com

(See followup article here.)

(See followup article here.)

I wonder how many trademark practitioners around the world noticed when, on November 1, 2019, IP Australia became an Accessing Office in DAS for trademarks? Continue reading “Australia has joined DAS for trademarks”

Hello dear readers. By now you may have noticed the layout of the blog is back to normal. It will be recalled that a couple of days ago I had migrated this blog from a shared server to a dedicated server. As it turns out, one of the consequences of the migration was that the server defaults to a newer version of PHP. To get my regular WordPress theme functioning again, what I had to do is force it that this blog is running on a slightly older version of PHP. And indeed the theme functions again.

So now things are back to normal.

Why does the Ant-Like Persistence blog look strikingly different today? I did not want it to look different today but it does. I will explain why it looks different. Continue reading “WordPress Themes”

Well, folks, as I blogged here, the Offices that constitute the ID5 have one by one slowly made plans to become Depositing Offices and Accessing Offices in the DAS system. And for some time now, the sole remaining ID5 Office that had not made any public statement about plans to join the DAS system was EUIPO. The EUIPO has an Information Centre and every few months I make an inquiry to the Information Centre about this. In February of 2019, this was EUIPO’s official answer:

Well, folks, as I blogged here, the Offices that constitute the ID5 have one by one slowly made plans to become Depositing Offices and Accessing Offices in the DAS system. And for some time now, the sole remaining ID5 Office that had not made any public statement about plans to join the DAS system was EUIPO. The EUIPO has an Information Centre and every few months I make an inquiry to the Information Centre about this. In February of 2019, this was EUIPO’s official answer:

Your question is being taken into consideration by the EUIPO. We’ll contact you as soon as we have a definitive answer.

Not having heard back, last week I made inquiry again at the the Information Centre. And now I have received EUIPO’s official answer as to when it will join the DAS system for designs.

As US patent practitioners know very well, the chief database used by USPTO personnel to carry out most patent prosecution (including design patent prosecution) is called IFW (image file wrapper). Some nameless person at the USPTO made a decision back when IFW was being designed a decade ago, to make this a database in which no color or grayscale drawing would be displayed clearly. Instead any color or grayscale drawing will get blurred, often to the point of unrecognizability.

As US patent practitioners know very well, the chief database used by USPTO personnel to carry out most patent prosecution (including design patent prosecution) is called IFW (image file wrapper). Some nameless person at the USPTO made a decision back when IFW was being designed a decade ago, to make this a database in which no color or grayscale drawing would be displayed clearly. Instead any color or grayscale drawing will get blurred, often to the point of unrecognizability.

Which then raises the question, how may a member of the public obtain a PDF copy of an issued US design patent that shows the actual color or grayscale drawings instead of the blurred non-color drawings of IFW? Continue reading “How to get a decent PDF of a US design patent that is in color or grayscale”

(Revised to include many excellent thoughts from readers.)

One of the nicest things about working with sophisticated patent firms in other countries is that they will ask questions about US practice that make me try to collect my thoughts about particular points of US practice. I have a pending US case that has received an Advisory Action. Instructing counsel, located in Europe, asked just now whether I thought it would be better to file an RCE or a continuation application in that case. In this blog article I will try to list some of the factors that I think might nudge an applicant one way or the other on such a judgment call.

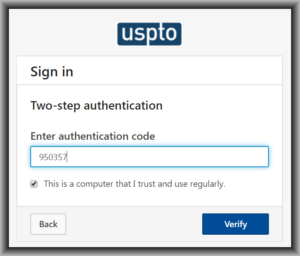

Last week I posted a blog article in which I explained that I had figured out why the check box doesn’t work. What USPTO says is that if you check the box, then for the next 24 hours you won’t have to do the two-step authentication. What really happens is that this almost never works. My explanation, as detailed in that blog article, is that there is a sneeze sensor in the software and if you have the bad luck to sneeze before your next login, this negates the effect of checking the box.

What is very sad about this situation with this poorly designed USPTO software is that judging from the reader comments and from other comments that I received privately, my explanation, which was intended to be humorous, was apparently no less plausible than whatever the (unknown to anyone outside of the USPTO) true explanation is. Many people were taken in.

Yes that previous blog article was meant like a sort of April Fool’s Day article.

I dug around in my cookies and I found what I am confident is the cookie that supposedly protects the user from having to do two-factor authentication for 24 hours. Here is an example of such a cookie:

Name: TwoFactorToken

Content:

LhRlmjFejO7oXhVAsL0ALTLakL0uoSU6EfdQF4vUl+VK+++CkALV+TY8/QuRgPUKmcphLj2KU1xKk+qPK6uvJXGVRLyRmF8UmY0CzjKGR7VJeamcI484moLcci/pqI41RVk4fdCJ5BjomIgoidqUP1n7n3XOd7/zhMXPlS1V0kzagVru9JSHfdSZVwUQDf6jDX4oEbDHDSCiaqACeUyxsGEwnY4Kjvv0egb6Wf7Rdq1uGGE8l4co+5EYlaPLBCt18L3ieisrgwMkRLo5pgJu8HQ3XTB+3+VSKU5F0iaYXsrkn5emalQXzqAVr2Ql+YWwyf3s5jaIac1rXngcFxcMXTm0sfsPHUOPKHPTUmbI0=

Domain: .uspto.gov

Path: /

Send for: Secure connections only

Accessible to script: Yes

Created: Monday, November 4, 2019 at 11:06:24 AM

Expires: Tuesday, November 5, 2019 at 11:06:24 AM

The cookie is called “TwoFactorToken”. It expires 24 hours after being set. Any second-level domain within “.uspto.gov” is able to retrieve the cookie. Clearly USPTO encrypts the “content” field. I consider it very likely that the way it works is this.

At the time the user checks the box, the USPTO script interrogates the user’s web browser asking for every possible piece of information that it can extract from the browser. It turns out that any web site can ask your browser for quite a few things:

The USPTO script might collect all of these things, combine it with the MyUSPTO user ID, generate a nonce, and assemble this into a data bundle. The USPTO script would then encrypt the bundle, or extract a hash of the bundle, or encrypt a hash of the bundle, something like that. And the result is put it into the cookie such as the one quoted above.

Then of course you get a forced logout after 30 minutes. So now it is time to log in again. The USPTO system asks for your user ID and password, and then the USPTO system has to decide whether or not it will force you to go through the two-factor authentication again. So it looks for the TwoFactorToken cookie. If there is no such cookie, then you have to do the two-factor authentication. If there is such a cookie, but it has expired, then you have to do the two-factor authentication. If there is such a cookie and it has not yet expired, then the USPTO system asks your browser for all of these things:

The USPTO system also looks to see what your user ID is that you are using to log in, and looks up the nonce that it stored in its local database relating to your user ID. The USPTO then then compares the answer that your web browser gave an hour ago with the answer that your web browser is giving right now.

Common sense tells you that many of these things are very unlikely to have changed during the past hour. Your operating system has probably not been upgraded during that time. Probably you have not updated your browser during that time. Maybe your list of installed plugins has not changed.

But your public IP address might well have changed. This might be because you logged into or out of a VPN. Or you physically moved from a Starbucks to your office. Maybe just moving from one location in your office to another location in your office could lead to your having a different public IP address. Moving from the secure network in your office to a guest network might well lead to a different public IP address.

And common sense tells you, the state of charge of your notebook computer battery is very likely to have changed during that hour. You may have plugged in your charger, or you may have unplugged your charger.

Also consider that you might have changed your screen resolution during that hour. By this we mean the screen resolution for the active window in your browser where the USPTO login was taking place. You might have resized a browser window for example.

Worse yet, suppose the USPTO local database containing your nonce is flaky. Suppose it often fails to respond promptly to a query from the login authentication software? Suppose it sometimes forgets the nonce?

Depending on how poorly the USPTO selected what to load into the cookie, any change to any of the things just mentioned could conceivably make the poorly designed USPTO software decide that you need to log in the hard way again. Maybe your battery ran down a bit during the past hour. Maybe you resized a browser window. Maybe you moved from your office to a Starbucks.

Or depending on how poorly the USPTO designed the local database that stores the nonces, maybe that by itself would explain why the checkbox often fails to work.

Until now, every Office that had become an Accessing Office for designs had previously been an Accessing Office for patents (except Canada). And until now, every Office that had become a Depositing Office for designs had previously been a Depositing Office for patents (except Canada). Continue reading “Canada joins DAS for patents as Accessing Office”

Until now, every Office that had become an Accessing Office for designs had previously been an Accessing Office for patents (except Canada). And until now, every Office that had become a Depositing Office for designs had previously been a Depositing Office for patents (except Canada). Continue reading “Canada joins DAS for patents as Accessing Office”

Monday, November 11, 2019 will be a federal holiday in the District of Columbia. This means the USPTO will be closed. This means that any action that would be due at the USPTO on November 11 will be timely if it is done by Tuesday, November 12, 2019.

For the past week the situation for e-filing at WIPO, for most people in the US, has been that the local time to e-file so as to get a same-day filing date in Switzerland has been different from usual. (The reason for this is that a week ago, people in Switzerland turned their clocks back.) But as of today, people in the US have turned their clocks back. So things are back to normal.

For the past week the situation for e-filing at WIPO, for most people in the US, has been that the local time to e-file so as to get a same-day filing date in Switzerland has been different from usual. (The reason for this is that a week ago, people in Switzerland turned their clocks back.) But as of today, people in the US have turned their clocks back. So things are back to normal.

For example if you are in the Mountain time zone, once again as of today you will be counting toward 4PM local time to get a same-day filing date in Switzerland. (For the past week the answer was 5PM.)