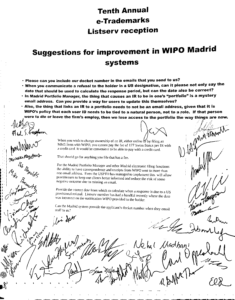

Hello dear readers. It will be recalled that on April 26, 2022, 42 PCT patent practitioners from the PCT Listserv signed and sent a letter to USPTO Director Kathi Vidal. The letter (click here to see it) has eight “asks” relating to the Patent Cooperation Treaty. As you can see here, what was really quite encouraging was that a mere two minutes later, Director Vidal responded, saying:

Thank you for reaching out on this … . I appreciate it. I will review it shortly. Kathi.

The part of the USPTO that is in charge of stuff like this is called International Patent Legal Administration (IPLA). A couple of days ago, the phone rang and it was a very nice fellow named Stefanos Karmis, who is the acting director of IPLA. He let me know that Director Vidal has asked him to be the point person on getting back to us on this letter. He asked if I could meet with him by telephone to discuss our “asks”. He and I have set a date of June 2 for a telephone call about this. This is, obviously, an encouraging development and we will want to do what we can to make the most of this telephone call, and whatever might come after that.

Here are some of the things that have taken place as part of preparing for the June 2 telephone call.

We have set up a private listserv for the 42 signers of the letter, so that we can discuss and prepare.

We have set up a Gotomeeting for May 26 for the 42 signers of the letter, so that we can discuss and prepare.

The other 900 or so members of the PCT Listserv who did not sign the letter (now I imagine some are wishing they had gotten off their behinds and signed the letter!) have been invited to get in touch with whichever of the 42 signers they are best acquainted with, to discuss and prepare. There may also be discussions on the PCT Listserv itself for discussions as we lead up to the June 2 phone call.