(Update: At the end of this article which I posted yesterday, I described a programming mistake in the newly released MAA software from WIPO. I wondered how long it would take for WIPO to get it fixed. Not even 24 hours have passed and already I received an email from a nice person at WIPO letting me know that they had fixed the problem. I tested and indeed it has been fixed.)

WIPO has just announced its new Madrid Application Assistant. Here is how WIPO describes it:

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has launched the Madrid Application Assistant, which automatically records all the information required to complete an international application.

The Madrid Application Assistant is the latest improvement to the service level of the Madrid Registry as part of WIPO’s drive to enhance the creation and management of trademark rights under the Madrid System.

You can see Information Notice No. 53/2020 and you can see a “learn more” page about the Madrid Application Assistant.

What exactly is this new Madrid Application Assistant? What is the problem, if any, for which the new Madrid Application Assistant is the solution? Who can use this tool? Is it a good idea to use this tool? Can applicants in the United States use this tool? How will this new tool affect US trademark practitioners? I will try to answer these questions.

To answer these questions it is helpful first to remind ourselves what “certification by the Office of Origin” means. By way of background, the Madrid Protocol came into effect in 1989. According to the Protocol, an applicant seeking to file an international trademark application under the Protocol cannot simply file the international application as a first filing. The applicant is required to have previously filed a domestic trademark application in the applicant’s home country. In the language of the Protocol, we say that the international application is tied to a “basic” application (or more than one “basic” application) which is required to have been filed in a trademark office where the applicant is a citizen or a domiciliary or where the applicant has “a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment”.

It is not the case that the “basic” application is required to have been filed within the past six months. Saying this differently, it is not required that the international trademark application claim priority (under Article 4 of the Paris Convention) from the basic application. (Although it is not required that the international application claim priority from the basic application, in a majority of filings the international application is filed within six months of the filing of the basic application and does indeed claim priority from it.)

The Protocol requires several conditions to be satisfied in the relationship between the basic application and the international application (“IA”). A first condition is that the applicant in in the IA is required to be the same applicant as the applicant in the basic application. A second condition is that the mark set forth in the IA must be the same mark as is set forth in the basic application. A third condition is that the goods and/or services set forth in the basic application must “cover” the goods and/or services set forth in the international application.

The Protocol also requires that subsequent events affecting the status of the basic application be reported to the International Bureau. As one example, if through “central attack” the basic application comes to be abandoned or canceled within the five-year “central attack” time period, the Protocol requires that this event be communicated to the IB so that the IB can report the event to the Designated Offices (the Offices that were designated in the international registration resulting from the IA).

The reader will realize that back in the 1980s when the designers of the Protocol were designing the Protocol, there was really only one way to satisfy all of these conditions and requirements, and that was to enlist the aid of the Office in which the basic application had been filed. Only that Office would be in a position to commit to the other Offices involved to report significant events regarding the basic application, such as its going abandoned or getting canceled. That Office would be ideally situated to carry out the detail-oriented comparisons between the basic application and the IA — the comparisons of the applicant name, the mark, and the goods and/or services. The terminology selected by the designers of the Protocol is that this Office is called the “Office of Origin” (“OoO”) and the carrying-out of the detail-oriented comparisons is called “certification”.

In practical terms, what happens is that the would-be applicant under the Madrid Protocol must file its IA in the OoO. the OoO certifies the application and forwards it to the IB. The OoO commits to the IB and to the other participants in the Madrid system that it will inform the IB of subsequent events relating to the basic application.

Some OoOs have systems by which the certification process takes place automatically. At the USPTO, for example, you can file what I call a “one-click” Madrid Protocol application. You go to an online system at the USPTO and enter the application number of your basic filing. The USPTO system auto-loads the applicant name and the drawing of the mark and the goods and services into the IA; the filer is not able to change those things. Because those things were auto-loaded, then by definition the IA satisfies the required conditions. This permits the USPTO system to automatically certify the application and it passes directly to the IB without any need for human handling at the USPTO. The USPTO passes along some of the savings in work by charging a cheaper certification fee for this kind of IA as compared with an IA in which the USPTO personnel must carry out the comparisons manually.

Many OoOs do not, however, have any e-filing system that brings about an automatic certification like this. At such Offices, the certification steps are necessarily carried out completely manually by human processing. For filings in such Offices, the application form (form MM2) gets filled out completely manually. Later, when money gets paid to the IB, the amount of money paid is manually determined by actions of the filer. It is easy to imagine many ways that mistakes can get made. The filer, filling out form MM2 by hunting and pecking at a typewriter, might get a character wrong in the applicant name. The filer might inadvertently characterize the mark as standard characters when in the basic filing it was stylized, or vice versa. The filer might inadvertently add some item of goods that is not exactly “covered” by the goods in the basic application. The human examiner at the OoO, carrying out the certification task, must necessarily proceed character by character through the entirety of the form MM2 from the top to the bottom, trying to catch any of these many kinds of potential mistakes.

Later when the time comes for the filer to transfer funds to the IB for the international filing fees, the filer might miscalculate the amount of the fees or might inadvertently transfer an incorrect amount of money.

The Madrid Application Assistant (“MAA”) is intended to minimize many of these potential mistakes and to save work for the OoO.

The way it works is this. The filer goes to the MAA system at WIPO’s web site. The filer indicates which Office is the OoO for the to-be-filed IA. The filer then provides the application number of the basic application. The MAA system then auto-populates the form MM2 using information drawn from an online database at the OoO. The filer then downloads a PDF of the form MM2 from the MAA system and submits this form MM2 to the OoO.

What we can appreciate from this is that for the person at the OoO whose job it is to carry out the certification, this makes the certification very easy. The applicant name matches because it was auto-loaded from the basic application. The mark matches because it was auto-loaded from the basic application. The goods and/or services match for the same reason.

The MAA approach also saves work for IB personnel who must review every incoming IA to see if there is anything wrong with it that the OoO might have missed. For example if the US is designated, the filer is supposed to provide form MM18. The filer might forget to provide form MM18, and the OoO might overlook this omission. In such a case, it would fall to the IB to detect the omission. But the MAA system forces the filer to provide Form MM18 if the filer designates the US.

When an IA that designates the US reaches the desk of an Examiner at the USPTO, what often happens is that the Examiner is forced to prepare and mail an Office Action asking the applicant to say what kind of legal entity it is, and where the legal entity was established. In the legacy approach with a manually completed form MM2, the filer might forget to provide these pieces of information. But the MAA system forces the filer to answer these questions from the outset. This saves work for the USPTO Examiner.

The MAA system calculates the fees payable to the IB, using fee amounts that are always up to date. Later when the IA gets certified to the IB, the IB can use the MAA system to collect those fees from the filer. This permits the IB to ensure that the correct amount of money gets paid, and makes it easy for the IB to match up the money with the particular application that just got filed. This is an improvement over the legacy practice in which the filer sends an amount of money that might not be the correct amount, and in which the IB must go on a treasure hunt every time a bank wire arrives, to try to guess which newly filed application is the correct application to which to post the payment.

Still another thing to consider is that conceivably a fee might change between the date that the form MM2 was generated, and the date of actual filing of the IA (the latter being determinative as to the amount of the fee actually due). The MAA system permits the IB to work out the correct fee amount based upon the actual IA filing date.

From the applicant’s point of view I do not see any drawbacks to the use of this MAA system. I see only potential advantages.

Who is able to use this MAA system? Here is a list of the eighty Offices of Origin for which the MAA system can presently be used:

- AF – Afghanistan

- AG – Antigua and Barbuda

- AL – Albania

- AM – Armenia

- AZ – Azerbaijan

- BG – Bulgaria

- BH – Bahrain

- BN – Brunei Darussalam

- BQ – Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba

- BT – Bhutan

- BW – Botswana

- BY – Belarus

- CO – Colombia

- CU – Cuba

- CW – Curacao

- CY – Cyprus

- DK – Denmark

- DZ – Algeria

- EG – Egypt

- ES – Spain

- FI – Finland

- GH – Ghana

- GM – Gambia

- GR – Greece

- HR – Croatia

- HU – Hungary

- ID – Indonesia

- IE – Ireland

- IL – Israel

- IR – Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- IS – Iceland

- IT – Italy

- JP – Japan

- KE – Kenya

- KG – Kyrgyzstan

- KH – Cambodia

- KP – Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

- KZ – Kazakhstan

- LA – Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- LI – Liechtenstein

- LR – Liberia

- LS – Lesotho

- LV – Latvia

- MC – Monaco

- MG – Madagascar

- MN – Mongolia

- MW – Malawi

- MX – Mexico

- MZ – Mozambique

- NA – Namibia

- NO – Norway

- OA – African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI)

- OM – Oman

- PH – Philippines

- PL – Poland

- PT – Portugal

- RO – Romania

- RS – Serbia

- RU – Russian Federation

- RW – Rwanda

- SD – Sudan

- SE – Sweden

- SI – Slovenia

- SK – Slovakia

- SL – Sierra Leone

- SM – San Marino

- ST – Sao Tome and Principe

- SX – Saint Martin

- SY – Syrian Arab Republic

- SZ – Swaziland

- TJ – Tajikistan

- TM – Turkmenistan

- TN – Tunisia

- TR – Turkey

- UA – Ukraine

- UZ – Uzbekistan

- VN – Viet Nam

- WS – Samoa

- ZM – Zambia

- ZW – Zimbabwe

The TM5 is defined as the five biggest trademark offices in terms of numbers of trademark filings. The membership in the TM5 is:

- CN – Chinese National Intellectual Property Administration

- EM – European Union Intellectual Property Office

- JP – Japanese Patent Office

- KR – Korean Intellectual Property Office

- US – United States Patent and Trademark Office

A natural question is how many of the TM5 Offices are available for filing using this MAA system? CN, EM, KR and US are not, because they have their own online e-filing systems. The USPTO, for example, already has the “one-click” auto-certified filing system mentioned above. US filers cannot use the MAA system, but that is not a problem since US filers have the one-click system which is just as good if not better.

If you are a potential Madrid Protocol applicant in any of the eighty countries listed above, it will be to your great advantage to consider using MAA to generate your Form MM2 and to pay your fees to the IB.

What are the likely consequences for US practitioners? A chief consequence will be that US practitioners will have less work to do. Until now, many Madrid Protocol cases designating the US ended up with Office Actions asking questions such as where the applicant was incorporated and what type of legal entity the applicant happens to be. But the validations carried out in the MAA workflow will force the filer to answer those questions from the outset. This will eliminate such Office Actions, meaning that US counsel will not need to be hired to respond to such Office Actions.

I tested the MAA system, using some randomly selected trademark filings in Denmark as the basic filing. It was very interesting to see that if I picked a basic filing that had gone abandoned or expired, the MAA system picked up on this and declined to permit me to proceed.

I picked a trademark registration of the well-known Lego company and clicked along until the MAA system gave me the auto-populated form MM2. You can see it here. You can see the applicant name and the mark and the goods, all of which were auto-populated into the form. You can see where the MAA system forced me to say where the applicant was incorporated and what kind of legal entity it is. You can see where the MAA system forced me to pick a second language for purposes of EM. You can see where the MAA system forced me to provide form MM18 for purposes of the US.

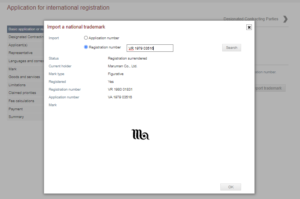

I found an apparent programming mistake in MAA. As you can see in this screen shot, I clicked to add a basic filing and I clicked the radio button saying that I was planning to provide a registration number rather than an application number. I then pasted “VR 1979 03516” into the box. This is a Danish registration in which the mark is the word “binky”. This should have brought up a registration number, not an application number.

I found an apparent programming mistake in MAA. As you can see in this screen shot, I clicked to add a basic filing and I clicked the radio button saying that I was planning to provide a registration number rather than an application number. I then pasted “VR 1979 03516” into the box. This is a Danish registration in which the mark is the word “binky”. This should have brought up a registration number, not an application number.

But what actually happened, as you can see, is that MAA retrieved application number 1979 03516 rather than registration number 1979 03516. The mark is completely different.

I wonder how long it will take for the Madrid Protocol people at the IB to fix this programming mistake?

Good news for trademarkers. Bad news for US trademark attorney.