One of the nice things about the patent system is that we can use the patent system to learn how stuff works. One of my favorite examples of this is the Zircon Stud Sensor. This product hit the market in about 1978, and I bought one of the first ones. The idea of the stud sensor was that it would tell you where the studs are behind a drywall sheet. You could then drive a nail or screw a screw into the wall, and hit the stud. You could then hang a heavy shelf on the wall and not worry that it would pull loose from the drywall panel.

One of the nice things about the patent system is that we can use the patent system to learn how stuff works. One of my favorite examples of this is the Zircon Stud Sensor. This product hit the market in about 1978, and I bought one of the first ones. The idea of the stud sensor was that it would tell you where the studs are behind a drywall sheet. You could then drive a nail or screw a screw into the wall, and hit the stud. You could then hang a heavy shelf on the wall and not worry that it would pull loose from the drywall panel.

At that time, the prior art included just two ways to find studs. One way was to use a  fiddly little magnet on a pivot (see photo, right) and you had to see if you could stumble upon one of the drywall screws somewhere in that great expanse of wall. If you found one of the drywall screws, the magnet would (might) move slightly.

fiddly little magnet on a pivot (see photo, right) and you had to see if you could stumble upon one of the drywall screws somewhere in that great expanse of wall. If you found one of the drywall screws, the magnet would (might) move slightly.

The other way was sort of like dowsing. You would rap sharply on the wall with your knuckles, listening to the sound. The sound would (supposedly) change slightly depending on whether you happened to rap directly on a stud or on a place between two studs. It would (supposedly) sound a bit more hollow or resonant if the place where you had rapped happened to be between two studs. (Some people would use the handle of a screwdriver to do the rapping, instead of a knuckle.)

Anyway, old-timers would swear by this approach. An old-timer would rap on the wall and listen alertly, and would then pick up a hammer and nail and drive the nail into the wall. And fully 50% of the time the nail would strike a stud. (The other 50% of the time, the nail would make a hole that would have to be patched and repainted since the hole was no good for supporting that shelf that we talked about above.)

So in about 1978 I purchased one of these Zircon Stud Sensors. And it was fabulous. The fiddly little pivoting magnet could only find the stud if you happened find a drywall screw somewhere in that big expanse of wall. But the Stud Sensor did not rely upon detecting metal! The Stud Sensor could actually detect the wood of the stud itself.

Yes, the Stud Sensor could tell the difference between a section of drywall that had air behind it, and a second of drywall that had wood behind it. The Stud Sensor could tell the difference between air and wood, on the other side of maybe 5/8 of an inch of drywall panel.

The fiddly little pivoting magnet had to be scanned up and down and right and left, in two dimensions, to eventually stumble upon one of the drywall screws. If you scanned with sweeps to far apart from one to the next, you might miss the drywall screw. The Stud Sensor, on the other hand, only needed to be slide left and right. It only had to be moved in one dimension. And there was no risk of missing what you were looking for. The Stud Sensor never failed to detect the stud.

In 1978 I wondered how it was that this super-clever piece of electronic equipment could somehow sense the difference between air and wood on the other side of maybe 5/8 of an inch of drywall panel? Did it emit X-rays and watch for reflected X-ray energy? If so, why did the device only cost $19 and why was it not festooned with scary safety warnings about risks of harm from X-ray exposure?

The answer could be gotten by looking at the product itself. It was marked with a patent number, to wit, US patent number 4,099,118. I got a copy of the patent and learned how the Stud Sensor works. (You can get a copy of the patent here.)

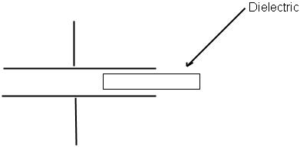

To understand how the Stud Sensor works, we can all recall that idyllic time in college when we took our first physics class. When we got to the section on electricity and magnetism, we all recall that fun homework problem where we were asked to work out the capacitance of a capacitor depending on the area of the capacitor plates, the spacing between the plates, and a third thing. Yes, there was a third thing that we had to know, in addition to the geometric measurements of the capacitor plates, to figure out what the capacitance of that capacitor was. The third thing that we had to know was the dielectric constant of the material that was located between the plates.

The simplest case was air. But you could also imagine the space between the plates was filled with glass, or some kind of plastic. If you knew the dielectric constant for the material between the plates, you could work out what the capacitance will turn out to be. Or (and this is the important part) if you are able to measure the capacitance of the capacitor, you can work the equation the other way and figure out what the dielectric constant must be for the material between the plates.

And there’s your answer. As explained in this patent, the Stud Sensor sort of opens up the capacitor plates and faces them both into the wall. The “stuff between the capacitor plates” is the drywall panel and whatever is behind the drywall panel. It might be air, it might be a wood stud. And the circuitry works out which is which by measuring the dielectric constant of that stuff.

At the time, my reaction was that the device is super clever. And I still feel that way now. The patent expired a long time ago, so anybody who wants to can make this kind of stud sensor. But I admire the inventor for inventing this device, and I admire this company for marketing it.

Touch displays, like the one present in most smartphones, also use this capacitive effect – very smart indeed and great progress compared to older resistive technology.