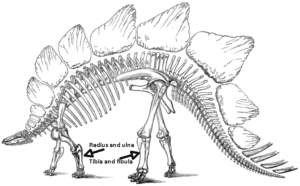

A few days ago I got to see Apex, which is thought to be the largest and one of the most complete stegosaurus specimens ever uncovered. I am sure that most museumgoers had the same reaction I had, which was a sense of profound wonder at the fact that the stegosaurus (and indeed nearly all dinosaurs) had a radius and ulna below the elbow of each forelimb, exactly like humans (and nearly all mammals), and had a tibia and fibula below the knee of each hindlimb, again exactly like humans.

Given that dinosaurs and mammals are different branches of the evolutionary family tree, separated for tens of millions of years, how can this possibly have worked out this way?

(By way of background, the word “ulna” means “elbow” in Latin. “Humerus” means “shoulder” in Latin. “Femur” means “thigh” in Latin. “Tibia” means “shin bone” in Latin. “Fibula” in Latin means “brooch”, somehow evoking the notion that the tibia and fibula together supposedly look like a clasp or brooch.)

We now return to the question presented. Given that dinosaurs and mammals are separate branches of the evolutionary family tree, how can this possibly have worked out this way?

People who do this stuff for a living (paleontologists) have arrived at consensus as to how this worked out this way. They have found what is believed to be the common ancestor of all tetrapods (animals having four limbs). This includes all dinosaurs and all mammals (and indeed all reptiles and birds and amphibians). This common ancestor is is a fleshy-finned fish, dating from the time of coelacanths and lungfishes, that lived between about 390 and 360 million years ago during the Devonian Period. This fish developed forelimbs with humerus, radius, and ulna, and hindlimbs with femur, tibia, and fibula (Wikipedia article).

The dinosaurs descended from this fish, as did all mammals and eventually humans. And they all have a radius and ulna and tibia and fibula.

Do paleontologists offer any suggestion of what evolutionary advantage that bone structure provided?

Interesting post and question! Google AI says “The advantage of having a radius and ulna is that these two bones in the forearm work together to enable smooth rotation of the wrist and hand, allowing for movements like pronation (turning your palm downwards) and supination (turning your palm upwards), due to the unique way they articulate and pivot around each other; essentially providing a wide range of motion at the wrist joint.” But for animals with paws or feet rather than hands it must be that they are still able to turn their paws or feet somewhat? For example, allowing our dog to firmly grasp a tennis ball and presumably actual prey between his front paws (and claws).

Evolutionary biology works in that traits that have a positive impact/benefit are selected because they provide an advantage to the organism. These traits are passed down and inherited to those animals and those species that may evolve from this common ancestor. The advantage of the evolved character may change over time, and it may continue to evolve, such that the trait may be used in different ways depending upon way the organism behaves or “operates” within its particular environment. But the essence of evolution is that common morphology (common traits) generally indicate common ancestry, you just have to go back far enough to find it.