We’ve become aware of a new trick that Examiners at the USPTO use to force an a pplicant to file an RCE. I hesitated for a while to blog about this, fearing that this blog article would educate any Examiners that did not already know about this trick. But hopefully the powers-that-be at the USPTO will read this blog article and will take appropriate steps to block the trick. And anyway maybe the word had gotten around the Examining Corps about this trick some time ago, and maybe there aren’t any Examiners that don’t already knew about this trick.

pplicant to file an RCE. I hesitated for a while to blog about this, fearing that this blog article would educate any Examiners that did not already know about this trick. But hopefully the powers-that-be at the USPTO will read this blog article and will take appropriate steps to block the trick. And anyway maybe the word had gotten around the Examining Corps about this trick some time ago, and maybe there aren’t any Examiners that don’t already knew about this trick.

The trick arises from the doctrine of OTDP (obviousness-type double patenting). Most of us have run into OTDP at one time or another. What happens is, an Office Action shows up from an Examiner. The Office Action contains a rejection of a claim in the case being examined, on the view that the claim presents a case of OTDP relative to some claim in some other application filed by the same applicant.

Such an Office Action helpfully explains that all that you need to do to make this problem go away is to file a TD (terminal disclaimer). But of course this isn’t true. The much bigger problem is that the two applications, previously being prosecuted independently of each other, are now suddenly closely linked due to the Examiner’s having mailed the Office Action that says what it says about OTDP. As of this moment, the applicant faces the problem that it is absolutely necessary to cross-cite every reference from either of the cases into the other of the cases, as soon as is humanly possible.

Note that this unhappy cross-citing burden is pretty much the same burden regardless of whether the OTDP problem is a real problem or is only an imagined problem. The mere fact that the Examiner said that the claims in the two cases are (supposedly) so closely related to each other is enough to force the cross-citing flurry of activity, regardless of whether it is actually true.

Failure to cross-cite every such reference would be begging for trouble at litigation time. At litigation time, if it were to develop that the applicant failed to cross-cite every reference, the accused infringer would argue that the fact that the claims are apparently so similar in the two cases that it triggered a finding of OTDP, is a fact that means that any reference that is pertinent to patentability in one case is automatically and necessarily pertinent to patentability in the other case.

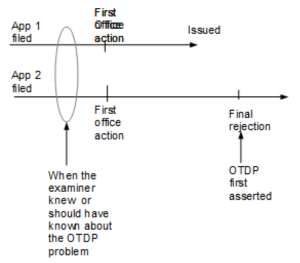

So let’s see how this works out in a real case. In a real case, like in the time line above, the high-volume corporate filer files Application 1 and Application 2 at around the same time (often, on the same day). The cases get classified differently and go to different art units and thus to different Examiners. Each case gets examined and each case receives a first Office Action in which various references are cited by the respective Examiner.

Nothing about the two applications particularly suggests to the practitioner in one case that the practitioner should pay any attention to the other case. The practitioner may not even know of the existence of the other case (as it may have been assigned to some other US patent firm).

Eventually the Examiner handling Application 2 mails out a Final Rejection. Maybe (as we have often seen) the case is perhaps said to be in condition for allowance except for this newly cited OTDP problem relative to Application 1. And the Office Action invites the practitioner in Application 2 to file a TD and the case can be allowed.

It is then up to the practitioner in Application 2 to snap to attention to the super-urgent need to cross-cite all references between the two applications. The practitioner looks up Application 1 in PAIR and prints out every IDS and every Form 892 that is of record in Application 1, arriving at a list of all references that have been made of record in Application 1. The practitioner repeats this process for Application 2, arriving at a second list. The two lists are then carefully compared and any duplicates on the two lists are crossed off the lists (because they will not need to be cross-cited). What’s left is a list of references from Application 1 that will need to be disclosed in Application 2, and a list of references from Application 2 that will need to be disclosed in Application 1.

Which is all fine and good, except that the IDS that the practitioner in Application 2 is getting ready to file in Application 2 is an IDS that won’t get considered by the Examiner unless an RCE is filed. The applicant has absolutely no choice but to file an RCE at this point.

It would be one thing if the Examiner could say with a straight face that only now at the time of the Final Rejection was the Examiner aware of the OTDP problem. But of course that is not how it really is. The real situation is that (as shown by the oval above) the Examiner actually knew, or should have known, of this OTDP relationship between the claims of the two applications way back at the time of the first Office Actions.

What you have, I suspect, is a situation where an Examiner knows perfectly well of an OTDP problem back at the time of the first Office Action. And the Examiner pulls the punch. The Examiner keeps the OTDP rejection in his or her back pocket until the time of the Final Office Action. As mentioned above, the consequence of keeping the OTDP in the back pocket permits the Examiner to force the application to file an RCE.

Of course this is piecemeal prosecution, which Examiners are not supposed to do. But Examiners can get away with it, as we at my firm have seen in several cases in the past couple of years.

Looking back over the time line, several things jump off the page about this.

First, of course, the Examiner knew or should have known about this real or imagined OTDP problem back before the first Office Action. If the Examiner had presented the OTDP problem back at the time of the first Office Action, then the practitioner could have filed the IDS at a time when a mere $180 fee would ensure consideration of the cross-cited references. Instead, because the Examiner kept mum about the OTDP problem until the Final Office Action, the only way to ensure consideration of the cross-cited references would be the filing of an RCE (at a cost of $1200 or $1700).

What should USPTO management do about this? Probably the way to fix this problem is to put a sentence into the MPEP that says that no Office Action presenting an OTDP problem is permitted to be “final”. This would permit the practitioner to ensure consideration of the cross-cited references by payment of a mere $180 rather than having to spend $1200 or $1700 to bring about the consideration of the references.

Such a rule would motivate Examiners to come clean about any OTDP problem much earlier in the prosecution process, generally in the first Office Action. There would no longer be any gamesmanship advantage to by gained by keeping an OTDP problem in the Examiner’s back pocket for revelation in a final Office Action.

There’s another even more serious consequence of this Examiner trick. As you can see in the diagram above, it could easily work out that at the (belated) time that the Examiner presents the OTDP problem in Application 2, a patent (call it “Patent 1”) has already been granted in Application 1. This makes it impossible to cross-cite references from Application 2 into Application 1, for the simple reason that Application 1 is not pending any more.

This makes Patent 1 a “walking corpse”. If the patent owner ever were to run down to the court house and sue someone for infringing Patent 1, the accused infringer would have no difficulty devising invalidity arguments based upon the references that were made of record in Application 2 and that were never made of record in Application 1.

Yes, I know, this problem can be fixed for Patent 1 by requesting Supplementary Examination. For which the government fees are something like $19K!

A rule that any Office Action citing an OTDP problem cannot be “final”, that is, a rule that motivates the Examiner to come clean about the OTDP problem in the first Office Action rather than some later Office Action, would tend to “smoke out” any need for cross-citing of references early enough in the process that Patent 1 would no longer have to face the prospect of turning out to be a “walking corpse”.

USPTO management, let’s please put a new sentence in the MPEP to address this trick.

This is a really great article. I guess from a practitioner’s perspective, the best way to handle this is to be sure to file a timely IDS and to be sure to cross cite all references for cases that you think can be related.

Excellent Stuff!

Great Stuff!

Obviousness Double Patenting also takes a lot time to work on. If there were IDS, why not file at beginning at once?