We will all be affected by the inevitable growth of OTT (over-the-top) distribution of entertainment, both as intellectual property practitioners serving clients and as consumers watching the stuff.

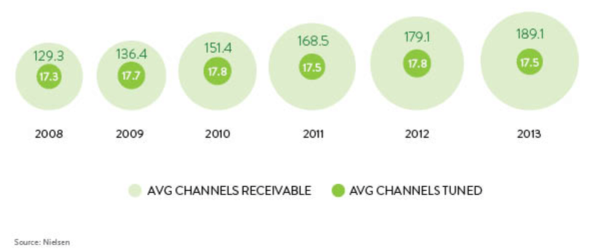

A Nielsen report from May of 2014 says that in 2013 the average American household got 189 channels from their cable television or satellite television provider, and actually watched only 17 channels. One way to look at this is that in 2013, the cable or satellite provider bundled about 112 channels that you didn’t want along with the 17 channels that you did want.

“Over-the-top” or OTT is the effort by some content providers to bypass the cable and satellite television providers and to reach consumers directly. I’ll discuss some of the OTT initiatives.

Perhaps the most visible OTT initiative is that of HBO (Home Box Office). HBO was founded in 1972, and for its first 42 years, was available only through cable and satellite providers. If you had an appropriate subscription package from a cable or satellite provider, you could watch HBO live. Using a DVR (digital video recorder) you could watch past episodes of HBO. And that was it. HBO had no direct sales relationship with viewers, and was completely beholden to a small handful of cable and satellite providers for its revenue stream.

In the fall of 2014, HBO for the first time made its programming available on demand over the Internet. Using an app called “HBO Go” in your media stick, you could watch current and past episodes of HBO programs on your HD television. This meant that you were no longer tied to a DVR if you wished to watch, say, last Sunday’s episode of Game of Thrones. And you could take your media stick with you to a friend’s home or along with you on your travels. The hitch? To get the app to work, you had to prove to the app that you were already paying for HBO’s channel on a cable television or satellite television service. HBO presumably designed the app this way so as to minimize the risk of alienating the cable television and satellite television providers that had made its existence possible for the previous forty-two years.

But HBO is slowly developing the resolve to go “over the top”, meaning that a would-be consumer of HBO’s programming could get the app to work by paying money directly to HBO rather than paying the money to a cable television or satellite television service provider. As of right now HBO’s toe in the water is “HBO Now” (not the same thing as “HBO Go”) which lets you pay $15 per month to iTunes so that an app on your laptop or desktop computer will let you watch HBO programs on demand. (The determined geek can then use any of several fiddly approaches to make the content visible on a regular HD television.) Apple negotiated a three-month period of exclusivity with HBO for “HBO Now”, after which HBO will be willing to receive money directly from consumers for this “HBO Now” service rather than filtering the money through iTunes.

But as of right now the convenient way to view HD-quality HBO programs on demand, namely through a media stick that is plugged into your HD television, works only through the “HBO Go” app which only works if you can prove that you already pay a cable television or satellite television provider for HBO programming. Presumably HBO will eventually develop the resolve to release an HBO Now app for media sticks, or will develop the resolve to let customers pay HBO directly to get HBO Go to work, at which point consumers will be able to pay HBO directly for the ability to watch HBO programs on demand on their HD televisions.

Another OTT initiative is CBS’s “CBS All Access”. For a $6 monthly fee, this service offers on-demand viewing of many CBS programs and (in many geographical areas) live viewing of CBS programming. As of right now the only media stick for which a CBS All Access app is available is the Roku media stick. Presumably CBS will eventually make the app available on other media sticks such as the Amazon Fire TV stick and maybe on blue-ray players and smart televisions.

Still another OTT initiative is Netflix’s streaming service. For an $8 monthly fee, this service offers on-demand viewing of many movies and Netflix’s own original programming such as the recent Marco Polo series. Netflix apps are available on all media sticks and blue-ray players and smart televisions.

Other video-on-demand initiatives include Hulu and Amazon’s streaming video services including the many television shows and movies available free of charge to Amazon Prime subscribers. The apps to get these services working are likewise available on all media sticks and blue-ray players and smart televisions.

For some consumers what is attractive about OTT offerings is that you don’t need a DVR. Meaning that you don’t need to worry about having failed to program or forgotten to program the DVR to record some particular show or series of interest. A DVR could crash (I have had this happen several times over the years) in which case the recorded shows are lost. And you don’t need to be in the same room as the DVR to watch an on-demand program. You only need to be in the same room with the media stick (which might be at a friend’s house or hotel room).

And if like me you don’t always catch on that some series is worth watching until after several episodes have aired, with an on-demand service you can go back and watch the series from the beginning, despite having failed to program that series into the DVR.

OTT is, of course, very popular with the “cord-cutters”, the consumers who choose not to subscribe to cable television or satellite television service providers. Recall the Neilsen report that I mentioned at the start of this blog posting. On average, American households pay for 189 channels and only view 17 of them. More and more of those 17 channels can be viewed through OTT offerings.

It is easy to imagine a transition to a future in which nobody pays for a channel they don’t want, nobody is tied to a DVR to watch past shows, and nobody has to be in the same room with a DVR or set-top box to watch programs that one has paid for. The transition will be extremely disruptive to many established industries and businesses, but seems inevitable. In that future, the cable and satellite providers would probably have little choice but to shift gradually away from bundles and toward à la carte offerings.

As an intellectual property practitioner I find it fascinating to watch the various media players jockeying for position and trying to test each others’ negotiating strengths. A recent struggle involves ESPN. ESPN has for years had the cushy position of being included in the basic bundle of channels for every cable and satellite provider. The cable or satellite provider has to pay quite a bit of money to ESPN to carry its channels, and has traditionally spread out that cost over a bundle of many channels. In an effort to move ever so slightly along the bundles-to- à-la-carte spectrum, Verizon recently announced that with its Fios television service, ESPN’s channels would no longer be part of the basic bundle but would be relegated to an optional sports bundle. ESPN has cried foul, saying that its existing agreements with cable and satellite providers require that ESPN’s channels be included in the basic bundle.

Sports programming is by far the biggest sticking point in this transition to OTT, and there are several reasons for this. For one thing, most sports enthusiasts are only interested in live viewing of a sporting event, not on-demand streaming of a sporting event from a week ago or a month ago. For another, the various organizations like MLB or the NFL or the NBA negotiate particularly complicated and restrictive contracts with the various networks and cable and satellite providers, contracts that do not easily or smoothly translate into OTT initiatives. As one example, when CBS announced CBS All Access, with live streaming of CBS content in selected geographic areas, CBS was forced to give the caveat that many sporting events would be missing from the live streaming. To see the sporting events, the customer would have to revert to an old-fashioned rabbit ears antenna or a traditional cable or satellite connection.

Intellectual property practitioners who negotiate licenses for media distribution are going to need a pretty good crystal ball to predict what the future will bring. License language that made sense in 2013 might not work at all in 2016.