One of my pastimes is trying to guess which sound bites, if uttered at a cocktail party, might lead to the turning of heads and might lead to other party guests clustering around with great interest. (See past blog articles.) Here is another: diatomic carbon.

Most of us spend our lives pretty much only learning about the things that happen at STP (standard temperature and pressure). Carbon finds itself in CO2, bonded with two oxygen atoms. Carbon finds itself in stable chains, and in our chemistry classes many of us memorized sequences of syllables such as “methane, ethane, propane” for molecules containing one, two, or three carbon atoms in stable forms at STP.

But there are chemists and physicists and (it turns out) astronomers whose daily life includes talking about the behavior of atoms under conditions that are way way different from STP.

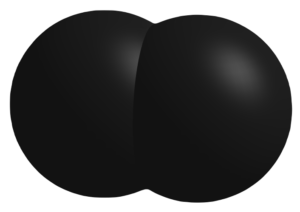

Which brings us to diatomic carbon (Wikipedia article).

It turns out that there is a particular comet that will pass closely enough to the Earth to be visible by the naked eye tomorrow (Wednesday, January 25) and Thursday (January 26), that previously passed near the Earth about 50000 years ago. Yes, apparently lots of astronomers have done the math on this and have worked backwards on when the exact time is that this particular comet most recently had its previous close visit to Earth, and the answer is 50000 years ago. And I am going to stick my neck out and guess that 50000 years from now will be the next time that this particular comet will next have a close visit to Earth.

Anyway, this particular comet, fetchingly named C/2022 E3, is green colored. And I gather it is green colored because it has some diatomic carbon in its trail, which is brought into existence in the extreme conditions of outer space because of energy from ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. (The extreme conditions of outer space are nowhere close to standard temperature and pressure, for those who are keeping score at home.)

Photons have various amounts of energy in them depending on their wavelengths. The shorter the wavelength, the higher the energy per photon. UV (ultraviolet) photons have pretty short wavelengths (compared with visible light) and so have quite a bit of energy per photon. This is why humans get sunburn and skin cancer from short-wave UV light, and it is why retired airline pilots get cataracts in whichever eye tended to be closest to the window when they were flying.

Anyway I gather that astronomers have worked out that it is short-wave UV light from the Sun that is striking this comet and causing carbon to break loose and form, wait for it, diatomic carbon in the head and tail of this comet. Which, I gather, has a green glow to it when seen in binoculars or maybe by the naked eye if you are very lucky in terms of being in a place that lacks light pollution.

And you know where I am going with this. Diatomic carbon is not stable at STP. So normal people rarely if ever encounter diatomic carbon in everyday life. There would be few daily activities in which one might have reason to mention to a friend or acquaintance that one had encountered diatomic carbon.

But if one happens to be at a cocktail party in the next week or so, maybe one might drop the sound bite “diatomic carbon”. The excuse being, of course, having gotten a glimpse of this very rare green comet.

My new go to astrophysical topic is from having recently learned that where I live in western NY, on my 70th birthday next year, there will be a total solar eclipse. I’m not sure what that portends though. But I’ll put on my welding helmet and have a look.

Of course, if you manage to view the comet and know the origin of the green tail, you can knowingly nod to an acquaintance at said cocktail party and say “did you C2?”

Oh took me a while. It’s a pun, folks. 🙂

Is this utterance the modern replacement for “Plastics?”

For younger readers, this is a reference to the classic film The Graduate.

All I need is clear skies which does not look like it will happen. 😩

If you have clear skies, get a free app called stellarium to find the comet. No need to pay for the enhanced version unless you are getting into astrophotography.

Thank you thank you you’ve been a wonderful audience 🤣

So cool!