It is as if the USPTO actively wishes to punish applicants for making the choice to use DAS instead of shipping a physical certified copy of a priority document. What I will now describe is a training fail for the USPTO’s Office of Patent Application Processing, along with a system design fail by the USPTO’s software developers.

By way of background, old-timers among the patent practitioner community will recall the old days when the standard way of perfecting a priority claim was:

-

- instructing foreign counsel would entrust to US counsel the task of filing a US patent application claiming foreign priority;

- instructing foreign counsel would obtain a physical certified copy of the priority application from the foreign patent office;

- instructing foreign counsel would dispatch the physical certified copy of the priority application to US counsel by international courier;

- US counsel would dispatch the physical certified copy of the priority application to the USPTO;

- USPTO personnel would remove the rivet and ribbon from the physical certified copy of the priority application, and would scan it into the US patent application file; and

- USPTO personnel would hand-key information into USPTO’s systems about the physical certified copy having been received.

With the advent of PDX (priority document exchange) and then with the advent of DAS (document access service), patent offices around the world, with the exception of the USPTO, have chosen to design their software systems to make intelligent use of automated processes to (a) deposit electronic certified copies of priority documents into the DAS system, and (b) retrieve electronic certified copies of priority documents from the DAS system.

For patent offices that have made such intelligent use of automated processes, and for the applicants transacting business with those patent offices, the DAS system has eliminated steps 2 through 6 listed above. This has been a positive-sum game (a “win-win”) in which the patent offices win and the applicants win. Nobody is worse off when the DAS system is made use of in an intelligent way by the patent offices involved.

When developers at the International Bureau of WIPO were initially designing the DAS system in 2008, they contacted me to get my input. My suggestions included the following:

-

- Applicants needed to be able to obtain some kind of proof from the DAS system that a particular accessing office really did have access to a particular priority application. Each accessing office would be aware that the applicant would be in possession of such proof-of-access, and would thus appreciate the inadvisability of playing dumb and pretending that it was somehow the applicant’s fault if the accessing office were to fail to carry out the retrieval of the particular priority application. This led to the availability of what is called a Certificate of Availability from the DAS system, which proves that a set of accessing offices really do have the ability to retrieve a particular priority application.

- There was a need for an applicant to be able to set up a sort of “trip wire” so that each time an accessing office were to retrieve an electronic certified copy, the applicant would be automatically notified (in real time) of the successful retrieval. Each accessing office would be aware that its retrieval would trip the “trip wire”, and that the applicant would instantly learn (in an automatic way) of the successful retrieval of a priority document, and would thus appreciate the inadvisability of playing dumb and pretending that it had supposedly been unsuccessful in carrying out the retrieval of the particular priority application. This led to the “Tracking” feature of the DAS system.

- There was a need for an applicant to be able to learn (in real time, in an automatic way) of any failure on the part of an accessing office to retrieve an electronic certified copy, along with diagnostic information as to the details of the failure. The diagnostic information as to the details of the failure would also be available to the accessing office itself. Each accessing office would be aware that if it were to make some mistake in its retrieval efforts, leading to a retrieval failure, the details of the mistake would be notified to the applicant. Each accessing office would be aware that if it were to make some mistake in its retrieval efforts, leading to a retrieval failure, the accessing office would have access itself to those details, permitting the accessing office to correct its mistake immediately. Each accessing office would thus appreciate the inadvisability of playing dumb and pretending that it was somehow the applicant’s fault if the accessing office were to fail to succeed in carrying out the retrieval of the particular priority application. This led to the “Notifications Log” feature of the DAS system. The Notifications Log is visible to the user and to the patent offices themselves.

The USPTO joined the DAS system on April 20, 2009, more than fourteen years ago.

Starting in 2018, the USPTO launched its DOCX initiative, which imposed and continues to impose substantial costs and burdens and malpractice risks upon applicants and practitioners, supposedly justified by the USPTO’s commitment to making use of computer-readable characters provided by applicants. The USPTO proclaims, to anyone who will listen, that it knows how to make intelligent use of computer-readable characters provided by applicants. The benefits to the USPTO of its intelligent use of computer-readable characters provided by applicants are (explains the USPTO) the justification for imposing those costs and burdens and malpractice risks upon the applicants and practitioners.

With this background in place, let’s see what sorry sequence of problems at the USPTO led to the retrieval failure memorialized in the screen shot at the top of this blog article.

It all started when trendy, modern, and up-to-date Dutch patent counsel filed the priority application, which was a Dutch patent application, on May 30, 2022. Following Best Practices in the Netherlands, when filing the priority application, the trendy, modern, and up-to-date Dutch patent counsel checked the relevant box of the application form indicating that the application should be made available to the DAS system. (Another option would have been to send a letter clearly stating the relevant application number and indicating that the application should be made available to the DAS system.)

About eleven months later, trendy, modern, and up-to-date Dutch patent counsel (our instructing counsel) entrusted to our firm the task of filing a US patent application claiming priority from the Dutch priority application. Following Best Practices, instructing counsel provided to us all of the information we would need to make use of the DAS system. One crucial piece of information was “the DAS Access Code”. The DAS Access Code is a four-character sequence which, when provided by our firm to the USPTO, permits the USPTO to retrieve the electronic certified copy of the priority application from the DAS system.

Members of the patent practitioner community who have attended my training events about the PCT and the ePCT system and the DAS system are aware that it is a Best Practice to make full use of the DAS system whenever a priority claim is being made. For a US practitioner who has been entrusted the work of filing a US patent application that makes a foreign priority claim, the Best Practices include:

-

- set up “Tracking” in the DAS system for the priority application;

- obtain a Certificate of Availability from the DAS system for the priority application; and

- pay attention to any notifications received from the DAS system that relate to the USPTO’s successful or unsuccessful retrieval attempts.

As soon as the instructions arrived from our Dutch instructing counsel, we did set up “Tracking” in the DAS system for the priority application. The very fact that we were successful in setting up the “Tracking” confirmed that instructing counsel had indeed communicated the DAS Access Code to our firm accurately. (If we had entered an erroneous purported DAS Access code into the DAS system for this priority application, then the DAS system would have reported an error to us rather than giving us the “Tracking”.)

One very interesting aspect of the “Tracking” in the DAS system is that it reveals if any other user of DAS has set up “Tracking”. The first thing that we saw when we set up our “Tracking” in DAS was that the Dutch patent firm had already set up “Tracking” in DAS for itself, for this priority application. As the alert reader will appreciate, this is yet another indication that the Dutch patent firm is trendy, modern, and up-to-date.

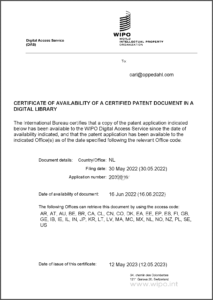

Our next step was to click an icon in the DAS system to obtain a Certificate of Availability for the Dutch priority application. At right you can see the Certificate. You can see that we obtained it on May 12, 2023. The Certificate proves that the priority application had been available to the USPTO since June 16, 2022.

The importance of this Certificate cannot be understated. It means that if at any time on or after June 16, 2022, the USPTO were to claim to be unable to retrieve this electronic certified copy, this Certificate would prove that claim to be unjustified.

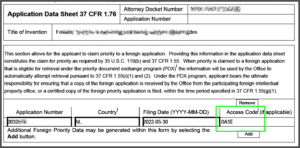

We filed the US application on May 12, 2023. The papers that we filed on that day included an express request that the USPTO carry out the retrieval of the electronic certified copy from the DAS system. You can see this in the Transaction History quoted at right. How did we communicate our express request that the USPTO carry out the retrieval of the electronic certified copy from the DAS system? We did it by means of the Application Data Sheet, quoted at right.

A normal, customer-friendly patent office would have acted upon the applicant’s request promptly after the applicant made the request. In this case, the customer-friendly retrieval of the electronic certified copy would have taken place soon after May 12, 2023.

But what we are looking at is the USPTO. For reasons known only to the USPTO, it foot-dragged the retrieval attempt until February 1, 2024.

One of the sad consequences of such foot-dragging by the USPTO is that it guarantees a failure on the part of the practitioner to have satisfied the dreaded “4-and-16 date”. The practitioner that fails to get the certified copy into the hands of the USPTO within 4 months of the US filing date, or within 16 months of the priority date (whichever is later) is deemed to have failed to perfect the priority claim. The sadness of this consequence cannot be overstated − if only the USPTO had carried out the retrieval attempt promptly after having been asked to do so (shortly after May 12, 2023), then any failure could have been promptly addressed and could have gotten straightened out before the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date. Instead, the USPTO foot-dragged the retrieval request until long after the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date. There is no excuse for this; most patent offices around the world do carry out their retrieval requests promptly after the applicant asks them to do so. Not so at the USPTO.

Ask yourself what a customer-friendly patent office would do in the event of a failed retrieval attempt. We all know the answer. The customer-friendly patent office would … wait for it … let the customer know promptly of the failure. Not so at the USPTO. The USPTO foot-drags any notification to the customer of such a failure. The first event at which the USPTO ever does the courtesy of telling the customer about the failure is the mailing of the first Office Action, in which the Examiner uses Box 12 of the Form PTO-326 to indicate whether the certified copy of the priority application has or has not been received. (This is almost surely well after the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date.)

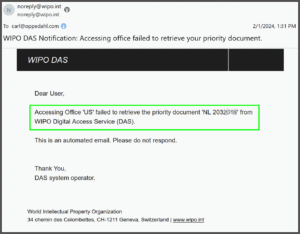

No, the USPTO did not do me the courtesy of letting me know if its failure, The only way that I came to know of the failed retrieval attempt was that I had set up a tripwire in DAS. (This is the “Tracking” mentioned above.) The USPTO tripped the tripwire. The nice folks at WIPO sent me the email message, quoted at right, to let me know of the failure.

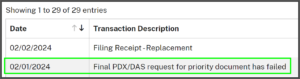

Prompted by the “Tracking” notification from DAS, I knew to look to see if anything in Patent Center might reveal the failure. And yes, we can see this information tucked away in the Transaction History, as shown at right. The USPTO says that the “Final PDX/DAS request for priority document has failed”. (The use of the word “Final” in the description suggests that maybe there had been some previous attempt by the USPTO to retrieve the electronic certified copy. There was no previous attempt.) This single attempt shown in the screen shot was the first and final attempt. The significance of the word “Final” is the USPTO’s way of saying it has no intention of trying again.

One assumes that if one were to ask the USPTO what went wrong in the retrieval attempt, the USPTO would fail to provide meaningful information, other than perhaps to try to finger-point in any direction other than itself. Finger-pointing opportunities would include:

-

- Maybe the foreign patent office failed to actually make the priority application available to DAS, despite having claimed to do so?

- Maybe the foreign patent office made a mistake when communicating the DAS Access code to foreign patent counsel?

- Maybe instructing foreign patent counsel made a mistake when communicating the DAS Access code, or the priority application number, or the priority filing date, to US patent counsel?

- Maybe US patent counsel made a mistake when communicating the DAS Access code, or the priority application number, or the priority filing date, to the USPTO?

Fortunately, when WIPO designed the DAS system back in 2008, WIPO provided the many safeguards that limit the availability of such finger-pointing. The “Tracking” feature, the Certificate of Availability, and the Notifications Log all limit the availability of such finger-pointing. As mentioned above, it is impossible for the practitioner even to set up the “Tracking” except after accurately entering the DAS Access code, the priority application number, and the priority filing date into the DAS system. So the very fact of the practitioner having successfully set up “Tracking” proves that the practitioner is indeed in possession of the true DAS Access code, the true priority application number, and the true priority filing date. The practitioner can, if necessary, show the Certificate of Availability to the accessing patent office to prove that the practitioner is not making this up.

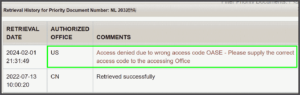

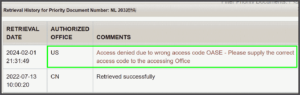

As mentioned above, the Notification Log of DAS, quoted at right, provides diagnostic information about the failed retrieval.

The DAS Access Code as provided by the Dutch patent office is a hexadecimal number. This means that each of the four characters in the DAS Access Code is selected from the ten decimal digits and from the letters A through F. This means, for example, that the letter “O” or the letter “S” would never appear in a DAS Access Code as provided by the Dutch patent office.

The alert reader will by now have figured out what the USPTO did wrong. The DAS Access code that I provided to the USPTO on May 12, 2023 was “0A5E” (zero A five E). It then fell to the Office of Patent Application Processing (the fancy name for the Application Branch) to carry out the retrieval. When the USPTO made its “first and final” attempt to retrieve the electronic certified copy from DAS, the USPTO’s Application Branch … wait for it … hand-keyed the DAS access code into the DAS system. And what the Application Branch hand-keyed was “OASE” (letter-O A letter-S E).

When we e-filed that ADS on May 12, 2023, we used the USPTO’s official XML-rich PDF form PTO/AIA/14. This form, a staggering 1.2 megabytes in size, preserves every piece of bibliographic information in XML (computer-readable) format inside the PDF file. The USPTO had and has available to it the text-based computer-readable characters of the DAS Access Code. There is no ambiguity about the DAS Access Code — the USPTO could even now obtain the “zero A five E” from the XML information that is inside that 1.2-megabyte computer file.

But no, the USPTO, which proclaims to anyone who will listen that it knows how to use characters provided by the applicant (for example in a DOCX-formatted patent application) failed to use the characters of the DAS access code that I provided on May 12, 2023. Instead, on February 1, 2024, what the USPTO clerk did was hand-keying the DAS access code. And the clerk did it wrong, failing to pay attention to the fact that because it is hexadecimal, it would be impossible for the first character to be a letter “O” and it would be impossible for the third character to be a letter “S”. I will give the clerk the benefit of the doubt with a high-confidence guess that the USPTO management never did any training at all about things like the DAS access code being hexadecimal.

But setting aside the likely failure to train properly, what is more serious is the USPTO’s failure to simply auto-load the computer-readable DAS access code from the XML content of the ADS into the DAS system. Had the USPTO done this, then the blunder of typing the “zero” as a letter O would never have happened, and the blunder of typing the “five” as a letter S would never have happened.

If this event (retrieving an electronic certified copy from DAS) were rare, then I suppose the USPTO’s software developers might be forgiven for failing to write the code to auto-load from the ADS to DAS. Why spend a few thousand dollars of programming money to eliminate risk of failures for an event that only takes place rarely? But this is an event that happens tens of thousands of times per year. Applicants file, in round terms, about half a million patent applications per year at the USPTO. About one-fifth of those applications state a foreign priority claim. In about 90% of those priority claims, the office of first filing is a Depositing Office in the DAS system, meaning that the US practitioner will be asking the USPTO to retrieve the electronic certified copy from the DAS system. This means that the event of an Application Branch clerk attempting a retrieval from the DAS system happens, as I say, many tens of thousands of times per year.

If there were ever a bad decision that got made at the USPTO, it was the bad decision to fail to spend the few thousand dollars of programming money to eliminate risks of failure for an event that happens tens of thousands of times per year. Instead, tens of thousands of times per year, a human clerk in the Application Branch hand-keys four characters of DAS Access Code into the DAS system. And as we see here, hand-keyed the zero as a letter “O” and hand-keyed the “five” as a letter “S”.

If only the USPTO had gotten the right answer instead of the wrong answer on this! Okay, let’s try to cut some slack for this wrong decision by the USPTO’s software developers. Maybe it only happened recently that the USPTO joined the DAS system, right? Nope. Sorry. As mentioned above, the USPTO joined the DAS system on April 20, 2009, more than fourteen years ago. The USPTO has foot-dragged this small bit of software coding for more than fourteen years.

Oh and imagine if the USPTO had done this small bit of coding a year ago, or fourteen years ago. Then what would follow automatically is … wait for it … the USPTO would be carrying out the retrieval attempts promptly after having received the retrieval requests. Most such retrieval requests would automatically happen well before the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date. Instead we have present USPTO practice which is to foot-drag the retrieval requests for months, often postponing the attempt until after the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date.

Let’s shine a bright light on yet one more management mistake at the USPTO regarding the DAS system. Recall that you, the alert reader, figured out ten minutes ago exactly what went wrong. You saw the screen shot of the Notification Log entry that showed the four characters that the USPTO clerk hand-keyed on February 1, 2024. You saw the screen shot of the ADS that showed the four characters that I provided to the USPTO on May 12, 2023. You saw that they did not match. You saw that it was a “5” and the USPTO clerk wrongly keyed an “S”.

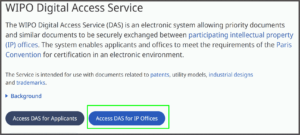

The yet one more management mistake at the USPTO about all of this is that when the USPTO fails to successfully retrieve an electronic certified copy from the DAS system, the correct next step is not to do nothing. That’s what actually happened. The USPTO did nothing. (The USPTO did not even do me the courtesy of communicating to me that its retrieval attempt had failed.) The correct next step for the USPTO is … wait for it … to log in at the DAS system and look in the Notification Log to see the diagnostic information. In the screen shot at right, you can see the big blue button in the DAS system bearing the legend “Access DAS for IP Offices”. Yes, USPTO management could have set up a business process rule requiring the USPTO clerk to click on this button, and to look at the diagnostic information. It took you, the alert reader, maybe a mere sixty seconds to figure out what went wrong at the USPTO. It would surely have taken the USPTO clerk only a minute or two to figure out the same thing. The clerk could then have slapped his or her forehead and could have said “oh I see it was a five, not an ‘S’!”

The yet one more management mistake at the USPTO about all of this is that when the USPTO fails to successfully retrieve an electronic certified copy from the DAS system, the correct next step is not to do nothing. That’s what actually happened. The USPTO did nothing. (The USPTO did not even do me the courtesy of communicating to me that its retrieval attempt had failed.) The correct next step for the USPTO is … wait for it … to log in at the DAS system and look in the Notification Log to see the diagnostic information. In the screen shot at right, you can see the big blue button in the DAS system bearing the legend “Access DAS for IP Offices”. Yes, USPTO management could have set up a business process rule requiring the USPTO clerk to click on this button, and to look at the diagnostic information. It took you, the alert reader, maybe a mere sixty seconds to figure out what went wrong at the USPTO. It would surely have taken the USPTO clerk only a minute or two to figure out the same thing. The clerk could then have slapped his or her forehead and could have said “oh I see it was a five, not an ‘S’!”

Such a business process rule would offer many downstream benefits. For example once a particular clerk caught on to what had been hand-keyed incorrectly, the clerk could share this with the other clerks in the Application Branch, and they all would have been able to watch for this mistake in their own hand-keyed DAS system work.

But from the point of view of serving one particular applicant (my client) well, instead of serving that one particular applicant very poorly, the simple step of clicking the “Access DAS for IP Offices” button ought to have happened on February 1, 2024. It ought to be standard practice at the USPTO that when a clerk fails in the retrieval attempt, the clerk ought to do that mouse click to figure out what the clerk did wrong.

If in this particular case I had used legacy practice, sending a physical certified copy of the Dutch priority application to the USPTO shortly after May 12, 2023, then I would never have had to deal with all of these USPTO mistakes and the attendant professional liability risks. The physical certified copy would have been safely lodged in the application file well before the expiration of the dreaded 4-and-16 date. Instead, I used the DAS system, and the USPTO punished me for it.

The USPTO’s failure to make nice with the DAS system is not limited to the wrong USPTO business decisions and bad USPTO training detailed above. The USPTO has also failed to become a Depositing Office in DAS for PCT applications filed at the RO/US. See this blog article describing that Thirty-One Patent Practitioners asked Acting Director Hirshfeld on February 22, 2020 to do this (see “ask” number 4). See this blog article describing that Forty-Two Practitioners asked Director Vidal on April 26, 2022 to do this (see “ask” number 8).

Have you faced USPTO failures with DAS retrieval? Do you have any reaction to what I described above? Please post a comment below,

I had a situation in which the DAS code was provided and acknowledged by the USPTO (as noted on the Filing Receipt and in the transaction history – 08/22/2022, Request for USPTO to retrieve priority docs) but the USPTO failed to ATTEMPT to retrieve the Priority Document. This was noted on the first office action by the Examiner. It required multiple calls (with extended wait times) to the Patent Office (Application Assistance Unit and Electronic Business Center). An “Escalation Ticket” was created and resubmitted. It was sent to a newly created team to expedite the retrieval. I was told that the priority document should have been automatically retrieved but would now be retrieved (but the Agent couldn’t promise) be available in the image file wrapper within 14 days. After monitoring via Patent Center, the priority document appeared in the image file wrapper (10/12/2023).

I found it interesting that the Chinese Patent Office had no problem quickly seeking the DAS priority application. That said, I suppose the next addition to best practices would be to set a tickler date in one’s docketing software for a date sometime prior to the critical 4 and 16 months to check the Notification Log of DAS to see if the USPTO has sought to retrieve the priority document. If not, then promptly contact the USPTO and prompt them to do so.

Good lord.

The USPTO seems to have gotten more openly hostile toward practitioners in recent years. They do not appear to consider or care about malpractice risks. (Why else provide no audit trail whatsoever for the DOCX file uploaded by the filer?) It almost seems like they enjoy setting traps and rejoice in “gotchas.”

The lack of communication is what gets me, and it’s not just here. As another example, in filing receipts, practitioners/applicants have to notice that the foreign filing license text is missing; the USPTO doesn’t include anything to help us, such as, “No foreign filing license granted.” How hard would it be to print something on the filing receipt??

And how hard would it be to put SOMETHING in the file history as soon as a PCT application gets stuck in national security review? But no, the application just sits there for no apparent reason, and they wait months to mail a piece of paper to tell the applicant that the application is stuck, and why.

I like patent law but I sure do dislike the USPTO these days.

We have made many phone calls to the USPTO ahead of waiting for an Office Action to inform us of success or failure. Unfortunately, we get a new person on each call that gives a different response from last person. With each call we have to start over with a new person at the Application Assistance Unit and Electronic Business Center, who are each unable to provide clear explanations or provide promises of resolution.

It would be nice if they had a DAS code department staffed with people properly trained on the topic.

I have recently seen several cases where the SB/39 was filed and acknowledged, or the ADS filed correctly, the USPTO even issued an updated filing receipt saying it was available but … neither IB nor EPO nor Chinese PTO were able to obtain the priority documents. This happened in various cases recently, with US priorities.

In one instance, the IB was able to obtain but the Chinese PTO was not.

In another, neither EP nor CN.

Very annoying and time consuming. and FRUSTRATING.

You didn’t say whether for each of your recent cases you had obtained “Certificates of Availability” from DAS. You didn’t say whether for each of your recent cases you had set up “Tracking” in DAS. I’d be grateful if you can expand on that part of the situation. What I have so often found to my detriment is that if one were to use only “information from the USPTO” in these situations, one can be sorely disappointed at the results.

Hi Carl,

For the one case where the IB was able to obtain yet CN was not: yes, in fact, I did have that, and had the tracking. Which I normally do.

The other cases were “takeovers”, i.e. I inherited them long after filing etc.

Correct, one cannot rely on the USPTO when it comes to DAS related info on a Filing Receipt.