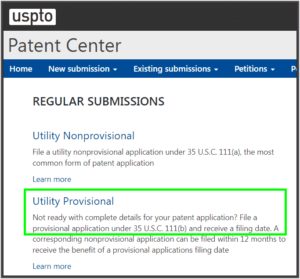

Folks, I have experimented quite a bit in the past 24 hours, trying to figure out a bit more about how to trick the clunky Patent Public Search system into yielding up answers for the 2022 toteboards. Here are my bits of incremental progress on ways to trick the PPS search system into giving you numbers that you might be able to use for the toteboards.

The date search portion of the search. To get patents issuing in calendar 2022, it looks like either of these search strings might work:

@PD>=”20220101″<=20221231

or

“2022”.py.

The latter is a smaller character count and is easier to type without error. Maybe it executes faster in the PPS system.

The application type or patent type portion of the search. To get, say, only utility patents, it looks like this might work:

(b1.AT. or b2.AT.)

This search string tries to get issued US utility patents that did not have a previous publication (B1) merged with issued US utility patents that did have a previous publication (B2).

To get, say, only plant patents, it looks like this might work:

(p2.at. or p3.at.)

This search string tries to get issued US plant patents that did not have a previous publication (P2) merged with issued US plant patents that did have a previous publication (P3).

To get, say, only design patents, it looks like this might work:

s.AT.

Recapping progress thus far. Thus for example if you want to know simply how many utility patents issued in 2022, it looks like this might work:

(b1.AT. or b2.AT.) and “2022”.py.

The answer seems to be 322992 issued utility patents in 2022.

The number of design patents might work with this:

s.AT. and “2022”.py.

The answer seems to be 34158 issued design patents in 2022.

The number of plant patents might work with this:

(p2.AT. or p3.AT.) and “2022”.py.

The answer seems to be 1072 issued plant patents in 2022.

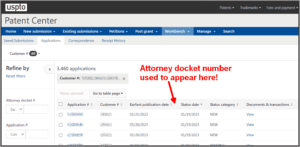

Narrowing it down to the firm name. We can then use any of the previous three search strings along with further field searching to try to narrow the search down to the firm name. The poor documentation for PPS suggests that any of the following might possibly yield legal-representative-specific results:

-

- .att. – said to mean “Attorney/agent/firm”

- .atty. – said to mean “Attorney name”

- .firm. – said to mean “Legal Firm Name”

- .inaa. – said to mean “Legal Representative or Inventor”

- .lrag. – said to mean “Legal Representative Name”

- .lrnm. – said to mean “Legal Representative Name”

- .lrfm. – said to mean “Legal Firm Name”

Within any one of these fields, the hapless searcher might want to try any of several proximity operators: ADJ, ADJ(n), NEAR, NEAR(n), WITH, WITH(n), SAME, or SAME(n). Some searchers will try AND within a field search. Toteboard searchers have tried strings including:

-

- (plinge AND llp).att.

- baker adj charlie.lrfm.

- (able and charlie).lrfm

Yes, it looks like you can omit the parentheses because I guess “ADJ” binds more strongly than the field name.

For our firm, the following search strings seemed to work:

-

- oppedahl.att. (“Attorney/agent/firm”)

- oppedahl.atty. (“Attorney name”)

- oppedahl.firm. (“Legal Firm Name”)

- oppedahl.lrfm. (“Legal Firm Name”)

The following search strings came up empty:

-

- oppedahl.inaa. (“Legal Representative or Inventor”)

- oppedahl.lrag. (“Legal Representative Name”)

- oppedahl.lrnm. (“Legal Representative Name”)

One firm tried a search like this:

(((“Plinge Patent Law”).firm. OR (“Plinge Patent Law”).inaa. OR (“Plinge Patent Law”).lrag. OR (“Plinge Patent Law”).lrnm. OR (“Plinge Patent Law”).lrfm. )

Part of what the firm was doing, I guess, was trying to get the benefit of any of the search fields that might possibly work (inaa, lrag, and so on). Another part of what the firm was doing, I guess, was to put three words of the firm name into quotation marks, to try to exclude nuisance hits from other firms with somewhat similar firm names.