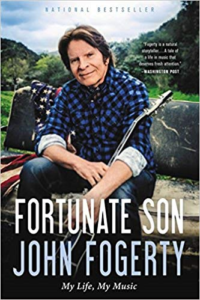

This book came out in 2016, and somehow I missed it. By accident I stumbled upon it a few days ago, and I could not put it down. I found it a fascinating autobiography by John Fogerty, the singer, songwriter, and guitar player for Creedence Clearwater Revival. Here are some of the songs that made CCR famous:

- Suzie Q (1968)

- Born on the Bayou (1969)

- Proud Mary (1969)

- Green River (1969)

- Bad Moon Rising (1969)

- Down on the Corner (1969)

- Fortunate Son (1969)

- Lookin’ out my Back Door (1970)

- Up Around the Bend (1970)

- Have you Ever Seen the Rain? (1970)

Fogerty wrote all but the first.

The members of Creedence, four sixteen-year-olds, signed a contract with Fantasy Records, which until then had made very little money. You know where this is going. The contract was stunningly favorable to the record company and gut-wrenchingly unfavorable to the sixteen-year-olds who signed it. Fantasy Records made more money in its first year with CCR than in all of the previous years of the company taken together. The following year, Fantasy Records made more money than the Beatles did that same year. The owners of Fantasy Records became fabulously wealthy, among other things becoming the producers of movies such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Imagine that it might possibly be interesting to read Mr. Fogerty’s memories of these and the many other events in his life and in the history of CCR.

But for those whose practice includes intellectual property law law, there’s more in Mr. Fogerty’s fascinating book.

Did I mention that Fantasy Records got the four sixteen-year-olds to sign a gut-wrenchingly unfavorable record contract? The contract not only gave ownership of all of those songs to Fantasy, but obligated the band to record many more albums, all of the rights to which would also go to Fantasy. Eventually after the passage of many years, and many lawsuits, Fogerty got once again to the point where he could write a new song and he would actually own the song that he had just written. But when he published the first such song, Fantasy sued him for copyright infringement. It was in the style of Fogerty’s original “swamp rock” songs (argued Fantasy) and so it infringed the copyrights in those songs, copyrights which were owned by Fogerty.

So there is a place in the book where Fogerty describes the trial in district court where the judge and the jury were asked to listen to the various songs and to decide (I am exaggerating only slightly) whether somehow Fantasy had a lock on every “swamp rock” style song that Fogerty would ever write during the rest of his life.

Fortunately the jury got the right answer on this. By having written and published his new song, Fogerty was not infringing the copyright on his old songs.

But I am not doing justice to this in my brief summary in this blog article. If you read this chapter of the book, you can live through, at least a little, what this trial was like for this song writer whose songs we have all heard and enjoyed so many times.

But that’s not all.

Recall that in most kinds of litigation in the US, there is “the American rule” which is that each side pays their own legal fees. But in a small handful of types of lawsuits, there are certain circumstances where the loser might have to pay the legal fees of the winner. For as long as there has been a US copyright law, it has been extremely well established that if a copyright owner sues an infringer, and wins, then if certain conditions are satisfied, the court will require that the infringer reimburse the copyright owner for its attorneys fees.

Which is all fine and good. What I find fascinating, however, is that apparently the first lawyer ever to read this provision of US copyright law really closely was John Fogerty’s lawyer. Yes, apparently until John Fogerty successfully defeated this meritless copyright infringement claim brought by Fantasy, nobody had ever paid close attention to the exact wording of this part of the US copyright law. John Fogerty’s lawyer, as far as I know, was the first lawyer who ever actually paid close attention to the fact that what it actually says is that the obligation to pay attorneys fees is symmetrical.

So, for apparently for the first time ever in the couple of centuries that we had had a US copyright system, a wrongfully accused copyright infringer had the bright idea of asking to be reimbursed for his legal fees. (By which I mean the lawyer representing the wrongfully accused copyright infringer.)

The US District Judge declined to award John Fogerty his attorneys fees against Fantasy. In retrospect this was clearly the wrong thing for the District Judge to have done, given that the law says what it says (and has said it for a couple of hundred years). But maybe the fact that District Judges in the past had (apparently) never before awarded attorneys fees to accused infringers in Fogerty’s position helped to explain the refusal of the District Judge to do what the law said.

Anyway Fogerty had the persistence to take this all the way to the Supreme Court, and now the situation is that every law school student sitting in copyright class learns about attorneys’ fees in copyright cases being payable to the prevailing party, and learns that the reason for this is the case of Fogerty v. Fantasy. But the student, sitting in that class, hearing that Supreme Court case being mentioned for sixty seconds after which the professor moves on to the next point, might have no sense of the extraordinarily rich and fascinating history behind that case.

Here’s your chance to read about it. And your chance to read a rich, warm, fascinating story of a talented musician and one of the most famous rock groups in history.

Sounds fascinating! Just ordered my copy, thanks!