Today I am working on getting ready to file a PCT patent application and I am filing it in DOCX and it reminds me how wrong-headed USPTO’s approach is. Folks, if you have not filed DOCX at the RO/IB, I invite you to try it so that you can see that there is a correct way to do DOCX. It’s just that the USPTO does not do it that way.

Again a bit of background. We all get it that it’s not a zero-sum game. Everybody can benefit from e-filing workflows in which the patent applicant provides characters rather than images to the patent office, and in which the characters get auto-loaded into patent office systems.

There are of course striking examples of patent offices getting this completely wrong. One example that has me gobsmacked is the USPTO system for the web-based issue fee payment (blog article). A filer who pays an issue fee using this web-based form provides characters to the USPTO, but then the USPTO flattens the characters to images. Then USPTO personnel hand-key the characters into the system that issues the patents.

Another gobsmacking example is USPTO’s web-based ADS for making changes to bibliographic data. Here, too, the user provides characters but the USPTO then flattens the characters to images then USPTO personnel hand-key the changes into Palm.

Back to the point of this blog article. Today I am getting ready to file a PCT patent application in the RO/IB. I have chosen to do it in DOCX. The ePCT system converts the DOCX file into XML and the XML is what gets used for the PCT publication that happens at about 18 months. Naturally the filer cannot help being apprehensive about the possibility that the conversion of DOCX to XML, and the later rendering of XML into human-readable ink-on-the-page for the PCT publication, might possibly lead to some unintended result. So what is designed into the PCT system to minimize that apprehension? It is called the “pre-conversion format” submission, as I will explain.

The way this works is that when I am assembling my ePCT submission package, one of the things that I am allowed to include, if I wish, is a ZIP file containing my “pre-conversion format” documents. This ZIP file can contain as many documents as I wish. In this particular case I chose to provide a ZIP file that contains a PDF of my figures in a very clear high resolution format, and that contains a PDF rendering of my word processor file that I rendered myself and that I trust because I did it myself.

Down the line, if it were to turn out that some oddity or corruption had occurred in the ePCT process of converting DOCX to XML, or if some oddity or corruption had occurred in the XML-to-ink-on-the-page process leading up to the PCT publication, I would be able to ask for this to be corrected. I would be able to point to the files that are inside the “pre-conversion format” ZIP file. If a math formula or chemical structure had gotten corrupted, I could drag in the original formula or structure from the ZIP file to fix it. If a Greek letter or square root sign had gotten changed into a smiley face, I could change it back by pointing to the ZIP file.

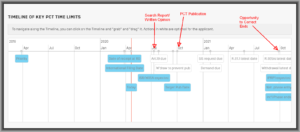

I say “down the line” but it is important to realize that under this PCT procedure, the opportunity to fix things is not open-ended. I would need to speak up before the end of the international phase, that is, within 30 months of the priority date (see time line at right). It is also important to keep in mind that there are at least two things going on that might provide opportunities to catch on about a need to fix something.

First, the International Searching Authority will have carried out the international search, mailing out the International Search Report and the Written Opinion. If there were some problem in the “ink on the page” as rendered by the ePCT system, this might come to light during the searching and examining activity by the ISA.

Second, the publication of the PCT application will have taken place at about 18 months after the priority date. The thoughtful filer will have placed a copy of the published PCT application under the nose of each of the inventors for them to review. This might smoke out rendering problems in the document. This also provides an ideal opportunity for the practitioner who wrote the patent application to read it again, taking a fresh look at the document many months later. The practitioner might be able to catch rendering problems. Others involved in the patent process might also take the time to look at the International Search Report and Written Opinion and the published patent application, prompted by this flurry of publication activity, and this might bring problems to light.

A third thing that can be kept in mind is that the filer simply has time for an unhurried review of things. If on the one hand the particular patent application was an uncomplicated document, then little or no review may be needed at all. If on the other hand the application was filled with unicode characters, math formulas, and many instances where meaning was communicated by position-sensitive formatting, then there will be many months during which to carry out an unhurried review. If a page break or font change or position shift somehow changed the meaning communicated by some combination of characters and lines and boxes, then there will be some months during which to notice it and to get it straightened out. If some math formula or chemical structure got corrupted, there will be some months to notice this.

Having said all of this, let me just mention in passing a few other really nice things about the ePCT e-filing system that I wish USPTO could emulate in its e-filing systems.

Click to see how it will get mangled. With EFS-Web, and unfortunately also with Patentcenter, the only way to find out how the USPTO system will mangle a drawing is … by clicking “submit”. Then you can go look in IFW and only then will you find out for the first time just how badly the USPTO mangled the drawing on its way to IFW.

What’s disappointing is that even after you see how badly mangled it is in IFW, this does not mean that it is as bad as it is going to be. When the USPTO publishes the patent application at 18 months, it is quite likely that the USPTO will mangle the drawing even worse than it was in IFW. And the only way you will find out how badly it will get mangled in the 18-month publication is … by waiting until 18 months.

In contrast, in the ePCT system, you can click and you can see a preview of how the drawings will be rendered for publication. You can see this before you click “submit” on your patent application. That way, if you decide you are not satisfied with how the drawings are going to look at publication time, you can back up and try to figure out what to do differently.

Why can’t the USPTO e-filing system do this?

By now I have been begging for this from the USPTO for something like twenty years. I actually got down on my knees in person in front of other people and begged for this from a particular USPTO person. This was about sixteen years ago. That USPTO person certainly recalls this. (This person’s initials are “H.E.”.) But it did not do any good. Even now, twenty years after the first time I asked for it, the USPTO still refuses to let you know how badly they will mangle your drawings until it is too late. And the USPTO mangles the drawings even worse for the 18-month publication, worse than they were mangled as they got inserted into IFW.

There’s one more really nice thing about ePCT that is missing from USPTO’s e-filing systems. A countdown. In this particular case that I am working on today, the underlying provisional patent application was filed April 24, 2019. Today when I logged in at ePCT, what popped up on the screen was a gentle “you can’t miss it” message that says:

Deadline to file this application to maintain the current priority date: Friday, 24 April 2020 24:00:00 CET

Tomorrow when I log in again, that message will pop up on the screen again.

Isn’t this nice? It’s the sort of thing computers are supposed to be good at. Why can’t the USPTO e-filing system do this?

Oh, and in the category of “you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar”, let’s talk about how WIPO handles DOCX and how USPTO proposes to handle DOCX.

USPTO’s idea of how to treat the applicant is that if you fail to file in DOCX, USPTO proposes to charge a $400 penalty.

WIPO’s idea of how to treat the applicant is that if you file in DOCX, you get a filing fee reduction of one hundred Swiss Francs (as compared with the filing fee that would be incurred if you e-file with a PDF patent application document). At today’s exchange rate that is a fee reduction of about $103.

What’s your reaction to all of this? Please post a comment below.

Agree 100%. No idea why the USPTO is obstinate about this.

The PCT approach to docx using the “pre-conversion format” is orders of magnitude better than the proposed USPTO pdf conversion tool that apparently will convert some portions of docx documents in unpredictable ways that result in serious errors in the pdf document.

Thanks Carl for the inspiring post. As to the EPO, they receive 82% as “PDF-text” (and 9% as PDF-Image”). Still, ” All incoming documents sent for Search Quality OCR” (Source: PPT “XML Filing and Exchange”, 18.01.2017). Raising the big question, why would PDF-text files be subjected to OCR? Unless of course, EPO throws away the text and stores the PDF files as images.