In our office we try to track pretty closely the status of the cases that we have put on the Patent Prosecution Highway. It is a rare PPH case that reaches its first Office Action without at least one problem within USPTO that requires us to poke the USPTO. Today one of our PPH cases presented a problem that we had not seen before — a big delay in examination because the USPTO misclassified the case.

This case had been made Special on the Patent Prosecution Highway in October of 2013 because of a favorable Written Opinion from a PCT Searching Authority. For a Special case, USPTO’s case management system normally starts ringing an alarm on the Examiner’s desk after a couple of months. So we should have seen an Office Action at least a month ago, maybe two months ago. But that only works if the case has been assigned to an Examiner. Often the USPTO first assigns the case to a SPE and then it is left to the SPE to figure out which Examiner in the SPE’s art unit should actually examine the case. This case got assigned to the SPE in a particular art unit. Let’s call him “SPE V”. It seems that SPE V decided that this case had been misclassified and should not have gone to his art unit. So he tried to get rid of it.

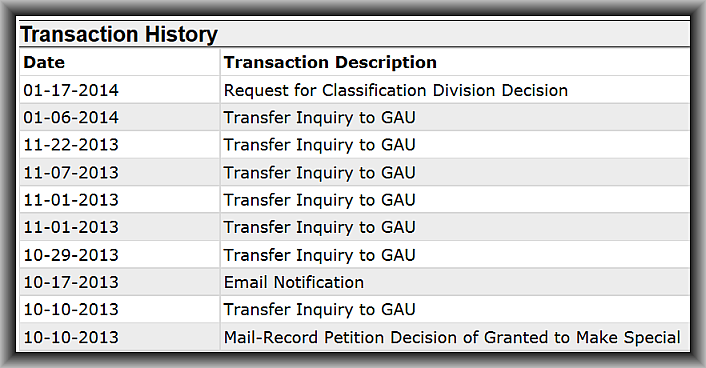

The normal way to get rid of an unwanted case (see MPEP § 903.08(d)) is to find some other SPE who will agree that his or her art unit ought to take the case. What we saw in the transaction history in PAIR was that SPE V has been trying to get rid of the case in this way for many months now. He first tried to get rid of the case on October 10 (shortly after it was made Special). He tried again on October 29, and then November 1, and then November 7, and then November 22, and again January 6. Apparently SPE V cannot find any other SPE who is willing to take the case.

Then on January 17 SPE V did something that I have never seen before in any transaction history of any file — a “request for classification division decision”. As the MPEP describes it this would be a decision of a “classification dispute technology center representative panel”.

Years ago the classification of newly filed US patent applications was done by USPTO employees. But at some point a decision got made within the USPTO to outsource the classification process for new patent applications. Since then, the classification has been carried out by a government contractor. The contractor often misclassifies cases — in our recent experience this happens about 10% of the time. When it happens, the case has to be transferred from one art unit to another. Normally this only delays things by a week or two. I am not sure what exactly went wrong with all seven of SPE V’s efforts to kick the case. But as of today he has not managed to get rid of the case despite four months of trying.

I looked at the case to see if it looks misclassified to me. And indeed it does look seriously misclassified. I can’t talk about the actual classes due to client confidentiality, but it is as if the claims were for television monitors and the USPTO’s contractor had classified it in technology for cross-country electrical transmission lines (that could be used for powering televisions or anything else). SPE V manages an art unit that knows what is patentable and what is not in the field of (say) cross-country transmission lines. And he would prefer that his art unit not be forced to try to figure out what is patentable and what is not in the field of (say) television monitors.

When I looked things up to see if I thought it looked misclassified, I was reminded how very poor the classification manuals and resources on the USPTO web site are. If you already know the US patent class and subclass, it is fairly easy to work out what the description is for that class and subclass. But going the other way is not easy at all. It is nearly impossible to do a meaningful text search or keyword search in the manual of classification. You have to sort of already know where in the manual your application belongs and then you go and look in that part of the manual to try to work out the subclass.

It’s been many, many years since USPTO did very much to improve its online classification resources. The reason for this is simple — USPTO knows that the days of the US patent classification system are numbered. It is only a matter of time (probably two or three years) before USPTO will scrap the US patent classification system and will slowly and foot-draggingly migrate over to the patent classification system that the rest of the world uses. (The system that the rest of the world uses is the IPC (international patent classification system).)

The application that SPE V is trying to get rid of is a US national phase from a PCT application. In January of 2012, as part of the PCT process the International Searching Authority already carried out the task of classifying this technology. The ISA (in this case, the Korean patent office) figured out that the case is in a particular international patent class. Yes, the ISA correctly figured out that the application had to do with television monitors (to use my example) rather than cross-country electrical transmission lines.

Anyway in this case the task of classifying this technology is work that already got done (and got done correctly) more than two years ago. But USPTO did not make any use of that work, and instead sent the task to a contractor who got it wrong. And the consequence is that our client has been denied the prompt prosecution that our client ought to have received on the Patent Prosecution Highway.

(Updated on February 23 to reflect that USPTO does have a limited “reverse concordance” which maps some IPC classes to corresponding USPC classes. Thanks to Louis Ventre, Jr. for kindly pointing this out.)

i had heard that US examiners were already getting training in the international classification system In preparation for the change over.

One of the attorneys at my firm mentioned that the US has already begun to convert to the CPC (Cooperative Patent Classification) system which is based off of the European Classification System (ECLA). The CPC is a bilateral classification system managed by both EPO and USPTO. Harmonization began in January 2013 and, after January 2015, USPTO search in CPC will be mandatory. I heard that CPC is specifically designed to be a powerful, flexible, and easily manageable classification scheme for internal, as well as external users. Perhaps these changes will prevent similar problems in other cases.

Yes your partner is correct that USPTO is moving that way. What’s very interesting is to see the difference between what the various classification systems are called and what they are.

The ECLA and the IPC seem to my eye to be about the same thing. Of course it would be politically impossible for EPO to adopt the USPC, just as it would (apparently, given this CPS fuss) be politically impossible for USPTO to adopt the IPC. So the face-saving approach is to pick a new name (CPC) that is not the same as either of the previous names. USPTO can then join EPO in “adopting” the CPC and this permits USPTO to save face. Meanwhile the EPO does not have to actually change anything substantive about how it classifies things.

If you spend a few minutes clicking around in the CPC what you will see is that it is the same as, or nearly the same as, the IPC. Class Go6F for example means the same thing in both systems — “electrical digital data processing”.

The CPC is based on the IPC, just as ECLA and Japanese F terms were based on the IPC. The difference is the level of detail (number of indents). The IPC is virtually useless for straight classification based searching since it never receives reclassifications and has only 60K subclasses. The CPC has much finer detail than the IPC or even the USPC.

It is hard for those of us with 10, 20, or 30 years of USPC experience to switch over, but the switch must be done and is generally quite painless. If you have a quality search tool (not uspto.gov), it’s also rather convenient to have the art from both the EPO and the USPTO classified in a single system. The other three biggies (JPO, KIPO, SIPO) will all be joining the CPC system soon as well.

More info is available at http://www.cpcinfo.org

Idk if your client was denied prompt examination. It looks to me like the examination is underway, classification is the first step and it is occurring, slowly but surely. You may have been denied a prompt action, but that is a different story.

Well, no, the case has not yet been assigned to any Examiner to be examined. As such, I don’t think it is fair to say that “examination is underway”.

Classification is supposed to take a few days, not four months. If we were to redefine “examination” as including this classification activity, then we would have to ask why it is that in this “special” case, the “examination” has not been done immediately as is supposed to happen in a case that is “special”.

The issue here is that the transfer inquiry process is fundamentally broken.

Generally what happens is that an examiner in the art unit either comes across a case while helping out with in-art-unit classification or receives a case on their docket. They realize that the case doesn’t belong in their art unit, so they initiate a transfer inquiry (either themselves or by contacting their SPE or an examiner in their AU who helps with classification). The transfer inquiry specifies a destination class and subclass, which is connected with a particular destination art unit. The SPE(s) or classifier(s) in the destination art unit then look at the transfer inquiry and decide whether or not the case belongs to them.

That’s the broken part. The first art unit, who are generally not experts in the correct art area, is stuck guessing the correct class and subclass for material they’re not really familiar with. If they guess wrong, the second art unit refuses the case, and if they’re feeling particularly helpful, will provide some other suggestions for the correct class and subclass. This is at the whim of the destination art unit. If the destination art unit decides they don’t feel like taking a case (and there are lots of reasons why they might do this, ranging from “it really doesn’t belong to us” to “being a jerk” to “your art unit gets more hours per case than ours, so you can keep it”), they can refuse it, even if they were the right place for it, and the first art unit is stuck trying to pass it off until (1) they find some other sucker who’ll take it, (2) the case goes through enough rounds of transfer inquiries to make a dispute resolution possible, or (3) they give up and work on it themselves.

This becomes even more problematic when a case straddles art areas or has no appropriate classification (or belongs in one so generic as to make it unclear that it actually belongs there). In these situations, it’s fairly likely that the wrong art unit will end up working on it, after several months are wasted with transfer inquiries.

What’s needed is a central authority that makes these classification/transfer decisions, taking away the destination art unit’s authority to refuse.

My understanding is that classification is based on the first paragraph of the application, the one that’s supposed to say the present invention (disclosure ) is directed to X and more particularly X + Y. If this paragraph is poorly written then you could well end up with a misclassification. It seems to me that many applications these days are a bit sloppy when it comes to what could be viewed as rote parts of the application (summary, abstract, and first para.). Do you think this could have been an issue in your case.

Yes especially a few decades ago the practice you describe was commonplace. In those days most patent applications filed in the USPTO were drafted by US practitioners and there was a long-standing tradition of (a) working out in advance the likely patent class and subclass, and (b) copying the description of the class and subclass into a first paragraph and (c) editing the copied words into the “is directed to … and more particularly …” format. Nowadays I don’t see this nearly so much in issued US patents (nor in published US patent applications). One reason for this is that many US patent applications filed nowadays are drafted by someone outside of the US who is drafting one document to be filed in many patent offices around the world. A second reason for this might be that (a) the US rules do not require it and (b) preparing such a paragraph takes time and money and (c) why prepare it if it costs money and is not required? I also note that if an applicant were to feel the wish to suggest a patent class and subclass to the USPTO, there is a place to do it in the Application Data Sheet.

Apparently this is not true. There is no place on the ADS for a classification.

Fascinating! Thank you for pointing this out. At the time that I made the link to the ADS, it had fields where the filer could provide a suggested class and subclass. Since then USPTO has revised the ADS form and it no longer has those fields.

Hi Carl. Thank you for bringing attention to this issue. This is a much larger problem than most practitioners realize, and a much larger problem than you yourself probably realize.

The new CPC is based on ECLA. The European examiners basically can take their sweet time in classifying and send the case to other examining arts to see what classes they want to add to make sure a relevant subclass is not missed. The US policy is to spend as little time as possible classifying, so much so that they hire contractors to do the work, often poorly.

Now with the CPC there arise new issues. The EPO has agreed (in principle) to severely decrease the time allotted for classification to put them on the same footing with the PTO. This means that classification quality will be likely to suffer worldwide when CPC is implemented.

The PTO examiners have a quota of cases to examine, and that quota is different based on the USPC class and subclass. So now with the new system and new rules of classification, in the future an examiner may get less time to examine the same case merely because of the change in how it is classified. There will inevitably be many other growing pains related to the new system.

The last thing I would add is that the CPC, like USPC, does not address technology that is explosively developing right now, for just one example, 3D printing and similar “additive manufacturing” methods. Do an art search for “3d printing” and you’ll find a hilarious number of different classifications of very similar technology, none of which really fit well. Trying to search any one of the various subclasses in IPC or CPC would be a waste of time. These technologies really need to have their own standalone classes and do not. There seems to be no attention paid to handling the classification of rapidly growing new technology with USPC or the new CPC.

No wonder my application took nine months to again out the case into “Request for Classification Division Decision”

wow!

Thanks