In the EFS-Web listserv, a practitioner posts this question:

We have decided to go paperless for the future and to destroy all of our archived paper files for the period since every application appears on the PTO PAIR Image File Wrapper. Does anyone know what date the PTO began imaging every application filed? I know for a while they were going back and imaging some files, but not all. I want to know after what date we can be confident that the image file wrapper is in PAIR.

In this blog post I will try to answer the “what date” question and I will offer a thought or two about how a practitioner might decide which files can be destroyed.

The practitioner’s question broadly stated, if I understand it, is “how do we know which paper files we can discard?”

And then it seems the practitioner is trying to rephrase this question as “is there a simple rule tied to the filing date that I can give to my staff so that they know which paper files we can discard?”

So there is some history here. The first cases to get into IFW were in a handful of biotech art units. This was around 2003 IIRC.

Later, gradually, it penetrated through most art units. But not in a consistent way. For example the US-national-phase cases got imaged last. So in a given art unit on a given date you might see that all of the 111a cases had been imaged and none of the 371 cases had yet been imaged.

One of the straggler areas was reissue. It took a long time for the reissue cases to get dragged kicking and screaming into IFW.

The design cases also took extra long to find their way into IFW.

I would not be a bit surprised if toward the end there were also a few Hyatt submarine cases from long ago that had never been imaged.

I surfed around in PAIR to pick out a few dates. The oldest case that our firm has in PAIR is in Series Code 6. It was filed in May of 1984 and its location is that it is in the Franconia archive (which means it is not in IFW). I worked my way up to Series Code 10 (filing dates as long ago as about 2002) and some are electronic and some are in Franconia. By Series Code 11 (filing dates as long ago as about 2005) it looks like all or nearly all are electronic.

Series Code 29 (design) dates from as long ago as 1995. It looks like starting in around 2006, the “29” cases were pretty consistently getting imaged.

So if you were to set a goal of using a filing date as the way to know whether or not a case is in IFW, I suppose the “safe” date might be around 2006.

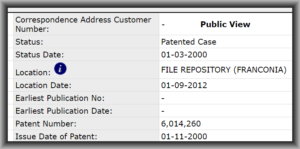

But it seems to me that if you want to give a simple rule to your staff, so that as they work though your old paper files, they know whether to throw them into the “these are in IFW” stack and the “these are not in IFW” stack, I don’t think filing date is the way to go. Indeed I don’t think any date-based rule is the way to go. The way to go, I suggest, is to just have a computer opened to PAIR. Plug in the application number and look at the “location” field. If the “location” is “electronic” then it is in IFW. If the “location” is not “electronic” then it is not. (Generally if it says something other than “electronic” then what it will say is “Franconia archive” as quoted above.)

But it seems to me that if you want to give a simple rule to your staff, so that as they work though your old paper files, they know whether to throw them into the “these are in IFW” stack and the “these are not in IFW” stack, I don’t think filing date is the way to go. Indeed I don’t think any date-based rule is the way to go. The way to go, I suggest, is to just have a computer opened to PAIR. Plug in the application number and look at the “location” field. If the “location” is “electronic” then it is in IFW. If the “location” is not “electronic” then it is not. (Generally if it says something other than “electronic” then what it will say is “Franconia archive” as quoted above.)

But it also seems to me that the “is it in IFW?” question is not really a good way to decide which files to preserve and which to discard. The thing is, if the file is not in IFW, you can say two things about it:

- You can say that it is in the Franconia archive, meaning that if you ever feel the need to do it, you can simply order up a copy of the file from the Office of Public Records. Yes it will cost $250 but you might only order up one such file wrapper ever in the years to come. Or two. But not twenty or a hundred.

- You can say that it is a really old file by now. Maybe it was filed 12 years ago, or maybe 15 years ago. The chances that you will ever feel that you need to reconstruct that file get smaller and smaller as the file gets older and older.

I suggest that to the extent you are looking for some situation at the USPTO that would allow you to give yourself permission to discard a paper file, the situation would not be “it is in IFW?” but rather “it is in IFW or I could order up a file wrapper?”. And the latter question may be answered “yes” for all of the US patent files that the practitioner is considering destroying.

The other thing of course is that particular states may have their own ethical rules that require an attorney to preserve a file for some number of years. The Colorado rule, for example, (oversimplifying) is that so far as the State of Colorado is concerned, you can destroy a file thirty days after you tell the client you are planning to destroy it (unless the client objects or unless there is a relevant threatened or pending proceeding). If you don’t feel like giving such notice to the client, you can destroy it ten years after the matter was closed (unless there is a relevant threatened or pending proceeding) unless for some reason you promised the client that you would preserve the file for a longer time.

How do you decide which old files you can destroy and which old files must be preserved? Please post a comment below.

The PAIR Image Wrapper is not the same as a client file, is it? Aren’t there other items in your client files, such as

client communication, memos, drafts, etc.? Also, when is a matter “closed”? After the patent is issued or perhaps after the

last maintenance fee is paid?

Before I started my own firm, I was an associate at Brumbaugh, Graves, Donohue and Raymond in Manhattan. IIRC the practice at that firm in those days (1993 or so) was that upon issuance of the patent the firm would “strip” the file. This basically meant that the “file wrapper” part of the file was discarded and the correspondence part of the file was sent to storage. (I don’t know how long the firm preserved the correspondence part.) The theory of course was that if it were ever to prove necessary to reconstruct the “file wrapper” part, the firm could simply order up a copy of the file wrapper from the USPTO.

It seems to me that even if one were to set a goal of preserving patent files for the longest time during which a question could arise, one could pretty safely toss the file once the patent-damages statute of limitations (six years) had run from the expiry date (which would be a function of which maintenance fee had or had not been paid).

I see no express, per se rule, for Virginia. The VA bar points to its Legal Ethics Opinion 1305. See http://www.vsb.org/profguides/closinglawpractice.html. LEO 1305 states in pertinent part “”In determining the appropriate length of time for retention or disposition of the remaining materials in a given file, a lawyer should exercise discretion based upon the nature and contents of the file. *** Finally, the Committee is of the opinion that the lawyer should preserve for an extended period of time an index of all files which have been destroyed.” This opinion also states “The lawyer should screen all closed files in order to ascertain whether they contain original documents or other property of the client, in which case the client should be notified of the existence of those materials and given the opportunity to claim them. Having culled those materials from the closed files, the lawyer should use care not to destroy or discard materials or information that the lawyer knows or should know may still be necessary or useful in the client’s matter for which the applicable statutory limitations period has not expired or which may not be readily available to the client through another source. Similarly, the lawyer should be cognizant of the need to preserve materials which relate to the nature and value of his legal services in the event of any action taken by the client against the lawyer. Having screened the files for the removal of any materials as indicated, the lawyer may at the appropriate time dispose of the remaining files in such a manner as to best protect the confidentiality of the contents.” There is an article on this issue for VA practitioners that contains useful practice points (which I have my firm follow). See “The Monster Called File Retention,” Wendy F. Inge, Virginia Lawyer, December 2012, Vol. 61, at http://m.vsb.org/docs/valawyermagazine/vl1212-risk.pdf.

The “file” belongs to the client. Usually the “file” includes not just what was filed in or received from the Office, but also confidential client communications, and perhaps drafts, work product, etc. Patent practitioners have an obligation under 37 CFR 11,115 and similar state court rules to safeguard client property.

A firm may decide on whatever metric works for it in terms of how long must the file be preserved and when can it be discarded or destroyed (some retention policies are set based on expiration of the statute of limitations for a legal malpractice claim). Whatever a firm decides, before it unilaterally decides to destroy client property, the firm should contact the client some reasonable time prior to your proposed destruction date advising the client of what your intentions are w/r/t the file unless they give contrary instructions by a date certain (and silence equals client consent). Another way you can get the client consent is in the engagement agreement. I have seen many engagement agreements that expressly discuss the firm’s retention policy regarding files and similarly provides the firm the right to destroy the file after patent issuance unless the firm receives written instructions to the contrary from the client within some fixed time frame, such as say three months or whatever after the patent issues.

In the UK, the statute of limitations sets a period of 6 years as the maximum time after an event involving a patent in which proceedings can be initiated. So a common policy is to keep files for 6 years after the expiry date.

Thank you for posting!